2018 has been a banner year for the job market. Job growth picked up and workers have continued to find jobs—a pleasant surprise at this point in the economic cycle. As the labor market has tightened, wage growth has definitively accelerated. The gains have been widely shared and there’s still room for the labor market to improve.

But this good news won’t go on forever—and maybe even not all the way through 2019. The sectors driving job growth today are projected to slow. An aging population too will limit job growth. And the Federal Reserve is likely to continue hiking interest rates, which could slow growth. Together, these looming headwinds mean 2019 probably won’t deliver like 2018.

What’s more, cracks are forming that could turn a smooth landing into a bumpy end. Growing geographic gaps, partisan disagreements, and policy uncertainties could make the eventual slowdown worse than it otherwise would be. No economic streak lasts forever, and no policy can make it do so. The big question for 2019 is whether this long recovery will end during the year. The more important question is whether the end — whenever it comes — will be graceful or ugly.

An impressive year for the labor market

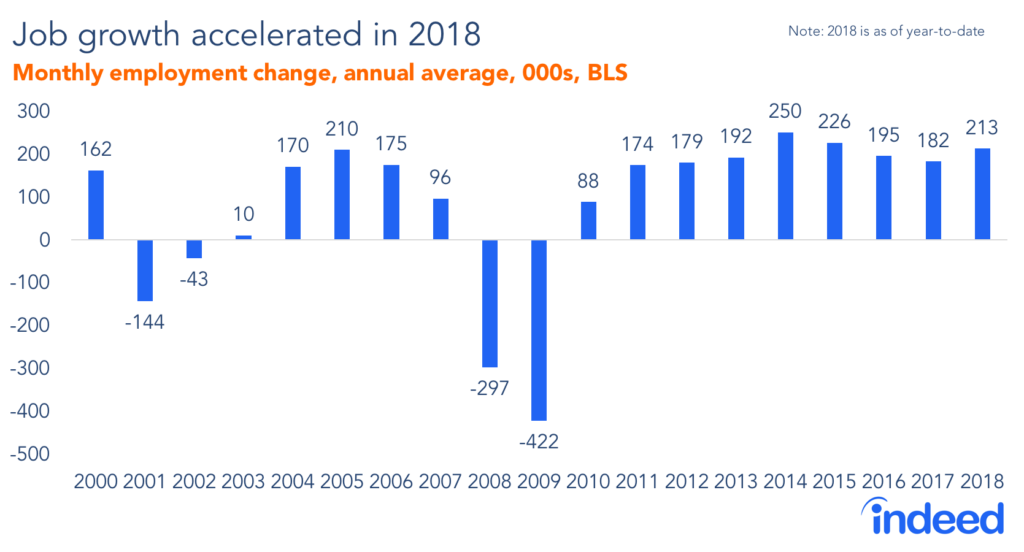

In 2018, the labor market fared better than anyone had a right to expect. Monthly payrolls grew by 213,000 on average. That’s faster than in 2016 and 2017 even though growth typically slows as a recovery ages and we get closer to full employment.

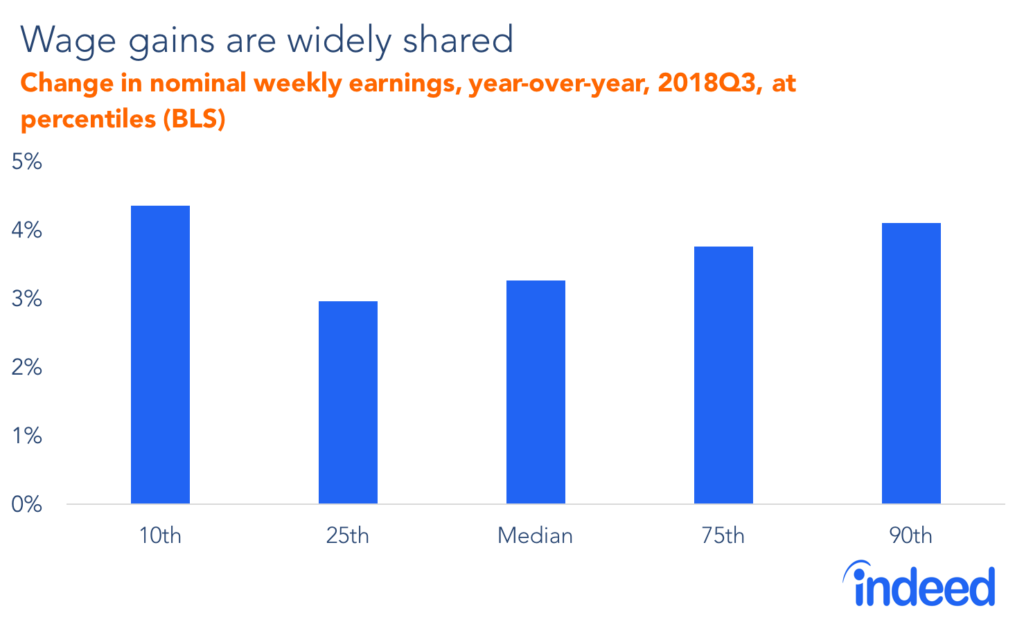

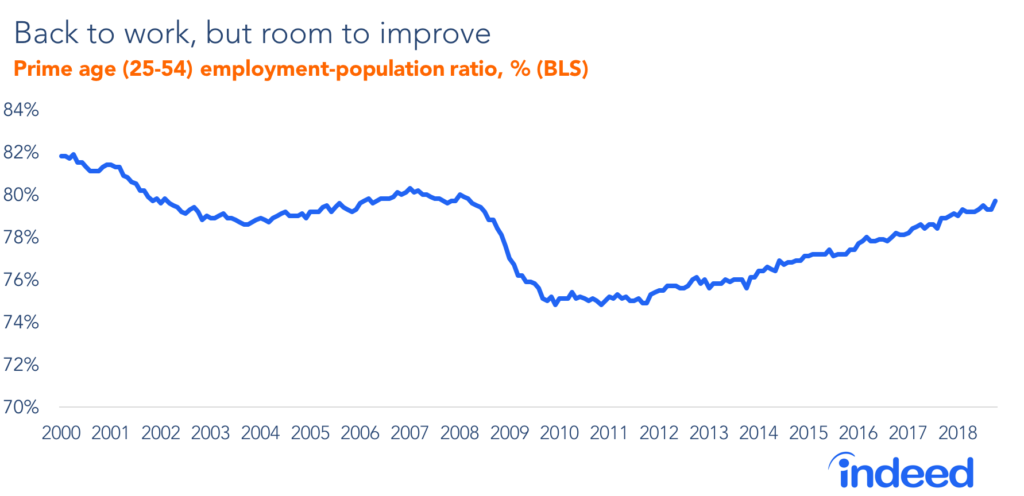

More people returned to work in 2018. The unemployment rate fell from 4.1% in December 2017 to 3.7% in October 2018—well below what the Federal Reserve thinks unemployment will be in the long run. A broader measure that includes labor force re-entrants—the ratio of employed people of prime working age (25 to 54) to their population—rose from 79.1% to 79.7%. And the share of workers involuntarily working part-time fell from 3.1% to 2.8%. Even better, the tightening labor market brought rising wage gains in 2018. Wage growth for private-sector workers topped 3% this year and looks to continue gaining next year.

Best of all, these gains were widely shared. Workers across the earnings distribution saw solid wage growth. The unemployment rate declined across gender, racial, and educational lines. In addition, retail sector job losses did not lead to a pickup in the unemployment rate for retail workers—an important reminder that when industry losses, like those in retail, are happening in a strong labor market, workers can find work in another sector. And the gains are reaching more corners of the country. Only two of the 100 largest metros lost jobs and employment is picking up even in left-behind rural areas.

To add to the good news, it looks like the economy still has room to run. Even though the headline unemployment rate is at its lowest since 1969, other labor market measures could improve further. The broader U-6 underemployment rate is only back down to its 2001 level. And the share of the population between 25 and 54 with a job has recovered only to its early 2008 level.

With all this momentum and room to grow, what could go wrong? So glad you asked.

The inevitable headwinds facing the labor market

Nothing lasts forever, including a booming labor market. There are several reasons why the recent years of labor-market growth probably can’t be sustained. Whether these reasons hit in 2019 or later, they will inevitably come—and hopefully will be gradual, gentle, and well anticipated. Two of these factors are rooted in long-term trends and shifts. The third factor—Fed rate hikes—is designed to prevent the economy from overheating.

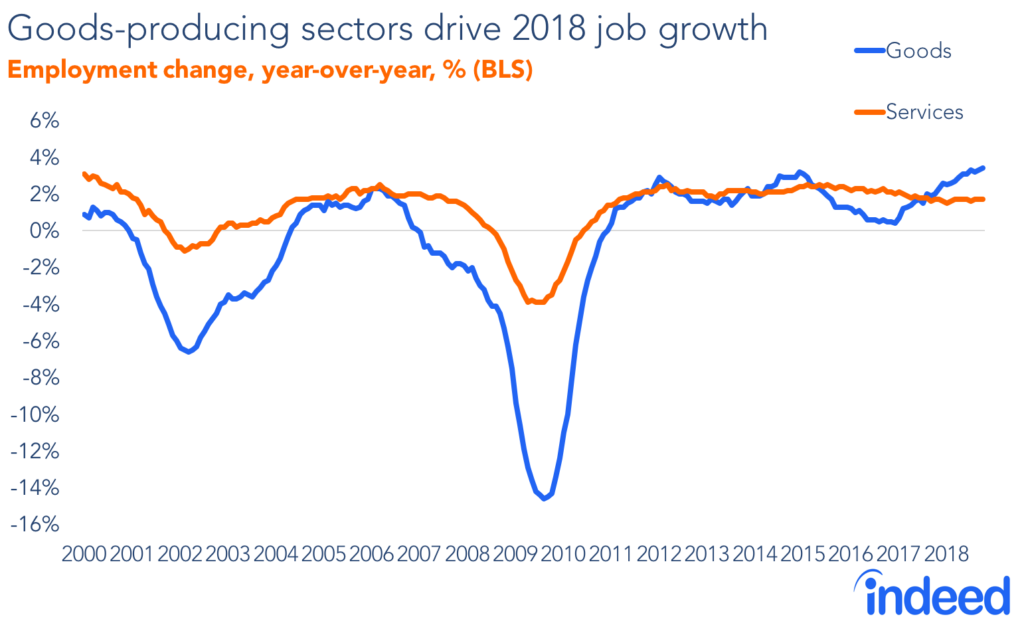

First: the sectors that led to extraordinary job growth in 2018 are volatile. The fastest-growing sectors have been mining and construction. And manufacturing has enjoyed a rebound after losing jobs in 2016. Together, these three goods-producing sectors have posted faster job growth than service-producing sectors. But goods sectors tend to bounce up and down. More worryingly, these goods-producing sectors are projected to grow only minimally longer-term. Nearly all US job growth is projected to come from service sectors, which are less at risk from automation or globalization than goods sectors are. Therefore, today’s goods-driven jobs boom is a precarious base for longer-term growth.

Second: the population is aging and the working-age population is growing slowly. Between now and 2030, the prime-working-age population of 25 to 54 year-olds is projected to grow just 0.5% per year. That’s much slower than in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, when working-age population growth averaged 1.8% per year. The economy needs only between 60,000 and 70,000 new jobs a month to keep up with this slowly growing population—way below the 200,000 per month range of recent years. The job market could sustainably grow faster than 60-70,000 per month if baby boomers delay retirement, working-age labor force participation rises, or immigration increases.

Third: the Federal Reserve may increase interest rates further. The tightening labor market already has the Fed concerned about the risk of higher wages and prices as employers compete for scarce workers. However, too many interest rate increases could slow growth. While the right number of rate hikes in 2019 remains a matter for debate, a tighter labor market makes rate increases more likely.

Together, the volatility of goods-sector employment, the slow-growing population, and Fed rate hikes will put limits on how long the labor market boom can go on. Ideally, these headwinds will be gradual and predictable.

The labor-market turbulence to worry about

Headwinds alone don’t make for a bumpy ride—but turbulence can. In 2019, turbulence could come from several factors. They’re not inevitable, but if they do materialize, the effects on the job market probably wouldn’t be as gentle or predictable as the headwinds just discussed.

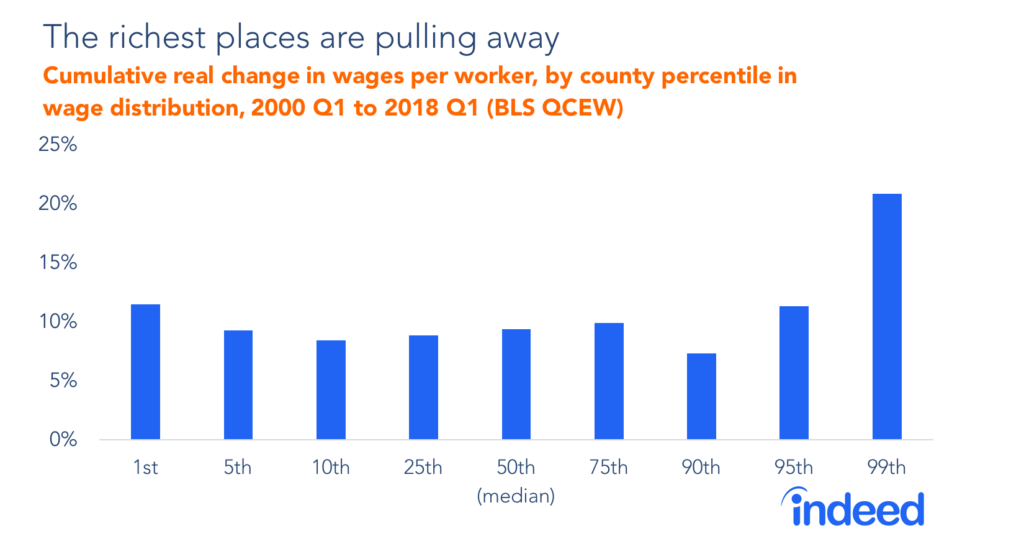

First: growing geographic inequality and partisan divides could make it harder to manage a slowdown. Even though recent labor-market gains have been widely shared, the richest places in America are pulling away from the rest. Wages have grown twice as fast in the richest counties— those at the 99th percentile—than in the rest of America, exacerbating geographic inequality. Amazon’s decision to put its additional headquarters in the rich, expensive metros of New York and Washington DC is only the latest symbol of widening geographic gaps.

These geographic differences are especially threatening because they follow partisan fault lines. Democratic-leaning areas inspire greater local economic confidence and are less at risk from automation. And when the good times end, there might be a political stalemate because no labor-market policy has solid bipartisan support. These geographic and partisan divides will make it challenging to manage the inevitable economic slowdown.

Second: the uncertainty from tax and tariff policies could weigh on the economy. The tax bill passed in December 2017 probably boosted the economy in 2018. But it won’t be able to spur growth forever. Its effects could begin tapering off as soon as next year. Meanwhile, the extent and effects of tariffs remain unclear. Tariffs might help some industries while hurting others. For instance, the solar and bourbon industries have not yet adjusted their job postings, but postings in the dairy industry are down since tariffs were imposed. Still, the first place to look for the effect of tariffs next year will be goods-producing sectors, which have led recent job growth and are inherently volatile. That means tariffs could compound the risk of depending on goods-producing sectors for continued job growth.

Third: several factors are aggravating slow growth of the labor force. The biggest wildcard is immigration policy. Increased immigration could expand the workforce, offsetting the effect of an aging population. But current policies are designed to reduce immigration, even though recent immigrants work in technical fields requiring specialized skills and have more education than native-born Americans. Furthermore, other factors prevent workers from going where opportunities are. High housing costs price people out of tight labor markets, licensing requirements make it hard for people to practice their crafts in new places, noncompete agreements make it harder to switch to higher-paying jobs, and ungenerous childcare and parental leave policies hold back female labor force participation.

The accelerating, widespread improvement in the labor market in 2018 is unlikely to continue in 2019 as the recovery ages. But there are still plenty of factors that might make the eventual slowdown better or worse than it otherwise would be. The big wildcards for 2019 are geographic and partisan divides, as well as taxes, tariffs, and policies affecting the supply and mobility of labor. They’ll determine whether the relatively predictable headwinds of goods-sector volatility, a slow-growing population, and further Fed rate hikes will lead to continued growth, a graceful slowdown, or a rough landing.