Key points:

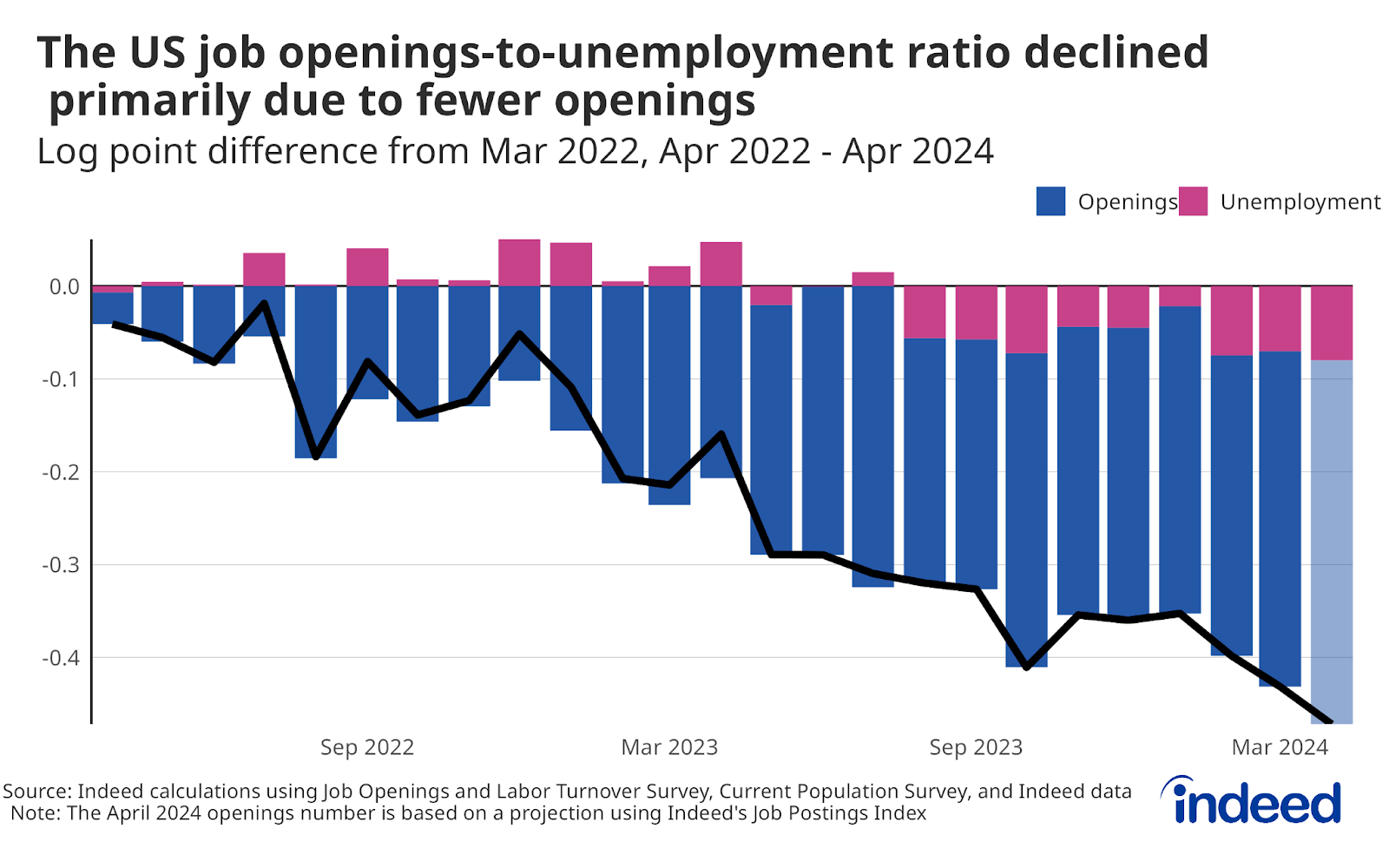

- Job openings have fallen more than 30% from their peak, but unemployment has only gradually drifted upward.

- A review of models from leading economists on the relationship between unemployment and job openings suggests job openings don’t have that much further to fall before returning to their relative balance circa 2019.

- However, a further decline in job openings would increase the risk that the current smooth moderation in the labor market turns into a more painful increase in unemployment.

Our monthly Labor Market Update looks at an important labor market trend, using Indeed and other labor market data. A more comprehensive view of the US labor market can be found in our US Labor Market Overview chartbook. Data from our Job Postings Index — which stands 14.4% above its pre-pandemic baseline as of May 10 — and the Indeed Wage Tracker are regularly updated and can be accessed on our data portal.

The US labor market was on fire in the spring of 2022. Wages were growing rapidly, workers were quitting their jobs at rates not seen in decades, and job openings outnumbered unemployed workers by a 2 to 1 margin. Unfortunately, inflation was also roaring, and the Federal Reserve made the decision to embark on a series of rapid interest rate hikes intended to cool inflation and bring down the economy’s overall temperature. Some two-plus years later the labor market has cooled considerably, but without a sharp rise in unemployment. This exceptionally rare feat has brought the labor market to the brink of a soft landing. However, further declines in job openings would increase the chances of significant turbulence.

Job openings don’t have much further to fall to return to the rough pre-pandemic balance between openings and unemployment, and by some measures may already be there. The ratio of job openings to unemployed workers fell to 1.3 in March, just above the 2019, pre-pandemic average of 1.2. The vast majority of that downturn has been driven by a decline in openings, which have fallen by more than 30% since March 2022, and which Indeed’s Job Posting Index (JPI) data suggest are continuing to fall. Many economists and commentators expected that bringing down this ratio from its 2022 highs would require a large rise in the unemployment rate. But that hasn’t been the case: The unemployment rate has only slowly drifted up over the past year and has remained below 4% for more than two years straight.

If we assume that the labor market in 2019 was well-balanced, then getting the ratio of job openings to unemployed workers (what we can call the V/U ratio) back to the then-prevailing level of 1.2 would seem to be a reasonable goal for policymakers. But it isn’t as simple as multiplying the current number of unemployed workers by 1.2 and backing out a reasonable target for job openings. A reduction in openings, all else being equal, generally means hiring will slow and unemployment will rise — potentially to the point where it risks cooling the market more than expected or desired. But, of course, not everything is equal. There’s reason to believe that when openings are elevated, unemployment will rise by a smaller amount for any given decline in the job opening rate. When competition for workers is fierce and job openings are high, a relative decline in openings from a high peak might not reduce hiring all that much. It’s the size of the hike in the unemployment rate in response to a decline in openings that’s been at the heart of the debate about the possibility of a labor market soft landing.

This debate is best exemplified by the back and forth between Federal Reserve Governor Christoper Waller and Federal Reserve economist Andrew Figura on one side, and Olivier Blanchard of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Alex Domash and Lawrence Summers of Harvard University on the other. Figura and Waller made an optimistic argument that the labor market could moderate primarily through lower job openings, with a relatively muted increase in unemployment. Blanchard, Domash, and Summers were more pessimistic, arguing the Fed could not push down vacancies without a notable rise in unemployment.

The past two years have mostly vindicated Figura and Waller, with the ratio of openings to unemployment currently at 1.3 and the unemployment rate at 3.9%. How much more might unemployment rise in order to finish this last mile and get the openings/unemployment ratio back to 1.2? Plugging the most recent data and a projection of April job openings using the Indeed Job Postings Index into models from both sides of the debate results in only a very modest increase in unemployment needed to bring the V/U ratio back to 1.2 The Blanchard, Domash, and Summers approach shows that the unemployment rate would nudge up to 4% while the Figura and Waller model shows a slightly larger increase needed, to 4.1%.

Turning those unemployment rates into the number of job openings at a 1.2 V/U ratio results in between 8 and 8.3 million openings needed to rebalance the labor market back to roughly 2019 levels. The latest job openings data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows there were 8.5 million openings at the end of March. Extrapolating openings data using JPI data projects that there were 8.2 million openings at the end of April. In short, job openings are on the precipice of reaching the range that would signal a return to 2019’s balance.

Many labor market indicators, including the quits rate, the hires rate, and even the unemployment rate, depict a US labor market that’s slightly cooler than it was in 2019. A return to the 2019 V/U ratio would represent the nail in the coffin of the idea that the labor market is currently overheated. But it would also signal that any further reduction in job openings could be a risky proposition, potentially shifting the so-far moderate rise in the unemployment rate into a much rockier ride upward. Monetary policymakers should be comforted by the labor market rebalancing that has already happened, but should also be alert to signs that their policies could be too restrictive for the labor market moving forward. A soft landing is in sight, but job openings will need to level off before we can safely touch the runway.

Methodology

The projection of April job openings was calculated using the number of job openings at the end of January 2020 (7.17 million) and multiplying it by the Indeed Job Postings Index number for April 30 (114.36) and dividing it by 100.

The Blanchard, Domash, and Summers calculation uses the method from this paper and plugs in the most recent data on hires, the labor force, unemployment, and the projection of the April 2024 job openings number. I also use a value of 0.4 for the parameter σ as they do in their paper. The Figura and Waller calculation uses the approach laid out in this note. I use their assumption of a matching efficiency parameter of 90% of its pre-COVID level, a value of 0.3 for the parameter σ, and a separation rate of 1.1 percent, which is roughly equal to the most recent share of employed workers moving into unemployment according to the April 2024 labor force flows data.