In April, the Australian federal government announced sweeping reforms to Temporary Work (Skilled) visas, better known as the 457 visa programme. The reforms, which include higher standards for English language competency and greater barriers to permanent residency, are relatively small in scope. But negative perception of the reforms may prove more harmful than the direct effects of the policy changes themselves.

Indeed is already seeing signs that some foreigners have been discouraged from seeking work in Australia: Clicks on Indeed Australian job postings from outside the country were 10% lower in June than in April, when the new policy was announced. This reverses the trend of recent years, when search activity in June was greater than in April.

The attention the 457 visa gets is disproportionate to its size or impact on the Australian economy. The programme is small in terms of the number of visa holders and as a share of total immigration. Nonetheless, the 457 visa has become the public face of immigration worries in Australia—and its first casualty.

A vigorous debate is underway on what 457 reform means for Australian businesses and the broader economy. Any discussion of visa reform should take into account the impact on Australia if outstanding foreign workers choose to go elsewhere for jobs.

Overview

Concern over the level of immigration has been on the rise in Australia, mirroring debates in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom. But Australia’s situation has its own unique features. Immigration has been a key driver of economic expansion over the past decade, pushing population growth well above the OECD average and offsetting weak productivity gains. Immigration reform has some support in Australia, but has prompted fears in the business community.

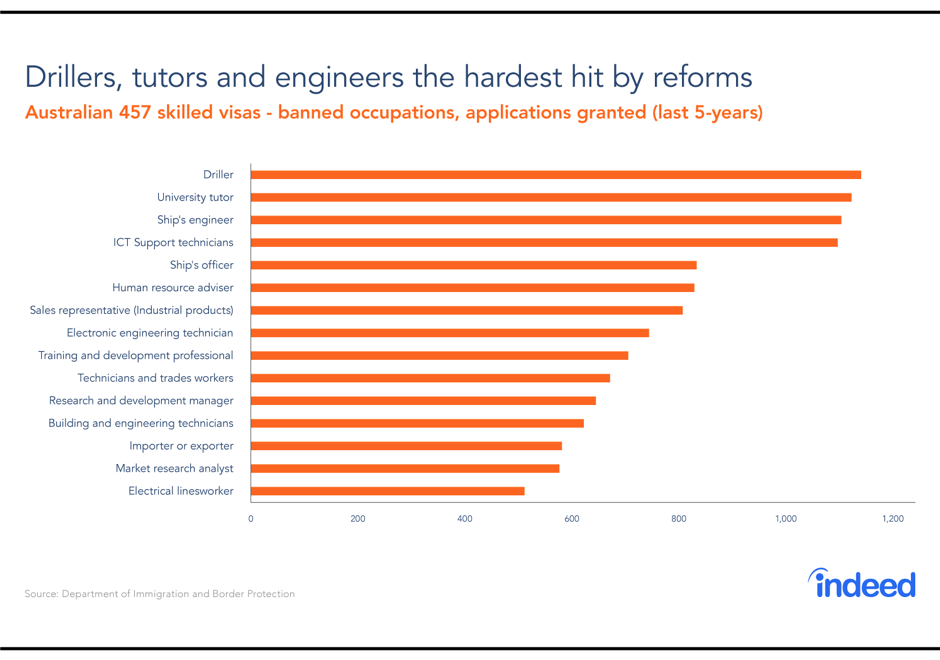

As part of the 457 programme reform package, the federal government banned almost 200 occupations from the visa application process. (Initially, 216 occupations were banned but the number was reduced on July 1.) The banned occupations have accounted for 7–9% of visas during the past five years. The list of eligible occupations will be revised on an ongoing basis every six months to respond to skill shortages that develop.

The reforms raise the hurdle for gaining a 457 visa in several other ways. Permanent residency has become harder to get and standards for English language competency are stricter. In addition, applicants must now be under age 45. Small businesses, those with under $1 million in turnover or five or fewer employees, face greater hiring restrictions.

Despite 457 visa reform’s relatively minor impact on the Australian economy, the changes could prove disruptive to certain industries and many individual businesses. There could also be a spillover effect: The high-profile nature of 457 reform may discourage foreign job seekers even in occupations that aren’t directly affected.

The technology sector, which faces widespread skills shortages, is a prime example. The reforms target few tech occupations. But the more difficult path to permanent residency is likely to make Australia less desirable for skilled tech workers. These workers are in great demand globally and many will choose to go elsewhere.

Size and Scope of the 457 Visa Programme

Department of Immigration and Border Protection data give a sense of the 457 visa programme’s reach:

- Primary 457 visa holders account for 0.8% of the Australian workforce.

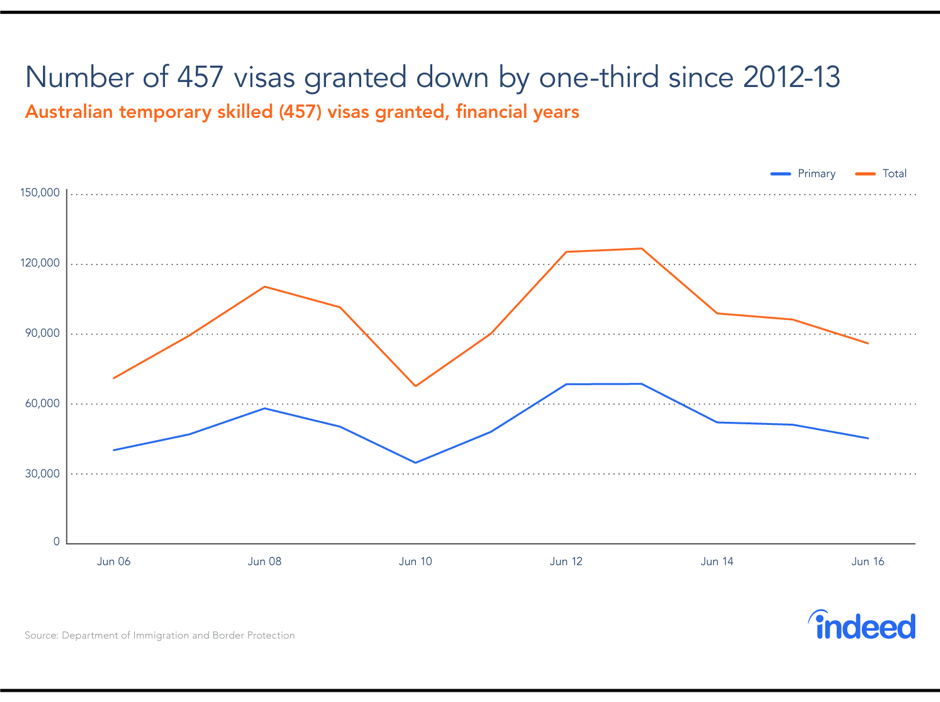

- The number of 457 visas granted has fallen a third from its peak in the 2012–13 financial year.

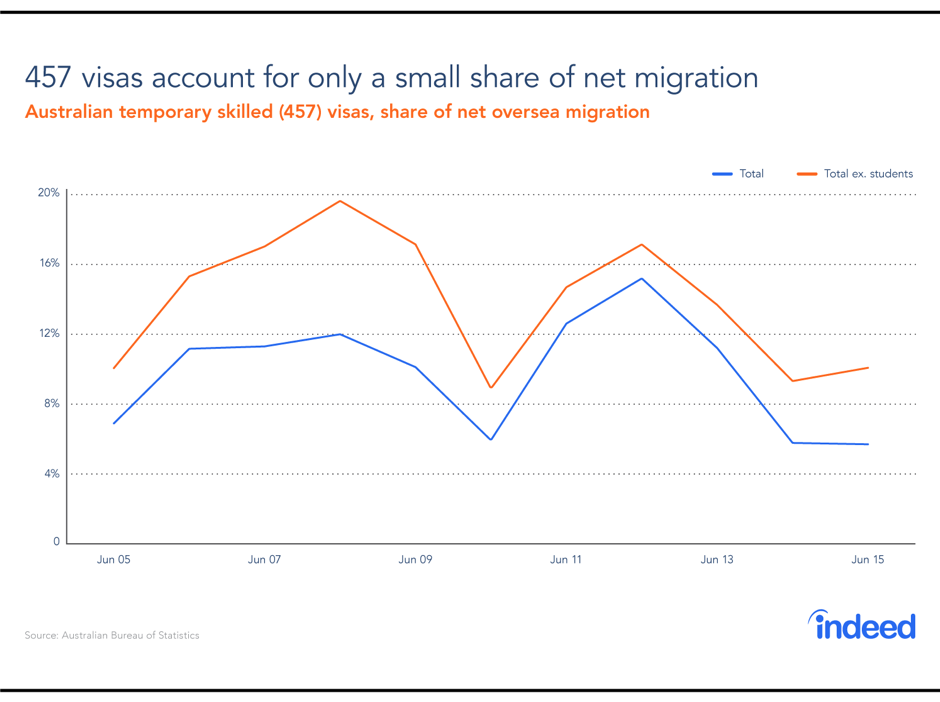

- 457 visa grants accounted for 5–6% of net overseas immigration in the 2013–14 and 2014–15 financial years.

- Those ages 25–34 represent around 62% of 457 visa holders, 35–44 year olds are 24% and those 45 or older are 7.6%.

- Around 25% of temporary skilled visa grants in 2015–16 came from India, 17% from the United Kingdom and 6.3% from China.

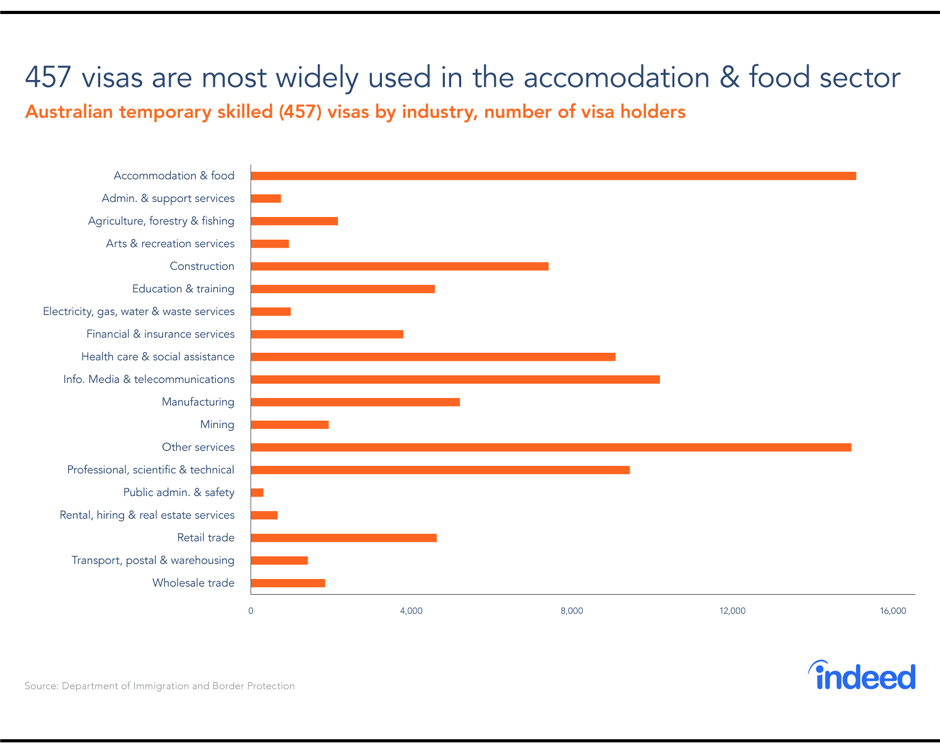

Hospitality and technology feature among the sectors that significantly rely on 457 visas. Cooks, developer programmers, café or restaurant managers, and ICT business analysts are the most common 457 occupations.

During the 2015–16 financial year, 45,395 primary 457 visas applications were granted. These awarded foreign workers the right to work in a specific occupation in Australia for up to two or up to four years. Most 457 visas go to applicants sponsored by an employer seeking to fill a particular role, with the four-year visas offering possible permanent residency.

A further 40,216 secondary applications were granted over the same period. Secondary applications cover family members or other approved individuals who accompany the primary visa holder.

The programme’s popularity grew following the global financial crisis. Foreign workers were keen to come to Australia thanks to a relatively strong economy and labour market, high wages and a strong Australian dollar. But, in recent years, Australia’s economic performance has been less stellar and the country has attracted fewer skilled foreign workers. The number of primary 457 visas granted has fallen by around a third since the 2012–13 financial year, coinciding with a fall in net overseas migration.

Over the past two years, the programme has accounted for between 5–6% of net overseas migration. That share represents a significant drop—it peaked around 15% in the 2011–12 financial year. At the end of March 2017, 95,360 people in Australia held a primary 457 visa and 75,341 had a secondary visa. Primary 457 visa holders accounted for 0.8% of the Australian labour force, down from a peak of 1% in the March quarter of 2014.

The Impact of 457 Reform

The federal government’s decision to ban nearly 200 occupations from the 457 visa program should reduce 457 grants by 7–9% annually based on historical trends. And the 45-year-old age limit should cut applications 6–8% annually.

The impact of reforms will be concentrated among a relatively small share of occupations. Around half the banned occupations have received fewer than 20 primary visas over the past five years. By contrast, 15 banned occupations have gotten 500 or more primary visas over the same period, accounting for over half of all applications granted to the banned group.

In other words, the changes are potentially disruptive for only a small number of occupations. And, as noted, the economic effects are minor, reflecting the fact that reforms are likely to cause a decline of 13–17% in a visa subclass that accounts for only 0.8% of Australia’s workforce. The 457 reforms are unlikely to move the needle much on overall employment, economic growth or even net overseas migration.

Nevertheless, indirect effects have the potential to create economically harmful uncertainty. In particular, the age limits, the higher standards for English language competency and greater barriers to permanent residency may deter outstanding foreign workers, as evidenced by the finding that Indeed Australian job postings registered 10% fewer clicks by job seekers outside the country in June than in April.

To be sure, evidence so far is preliminary and should be treated with caution. Nonetheless, the trend make sense in the context of the global market for skilled workers. Skilled workers are in high demand globally and can pick where they want to live and work. Indeed’s senior vice president Paul D’Arcy stressed this point during a recent visit to Australia. The perception that Australia has become inhospitable to migrants threatens to drive highly skilled foreign workers to other countries perceived as more friendly.