Key points:

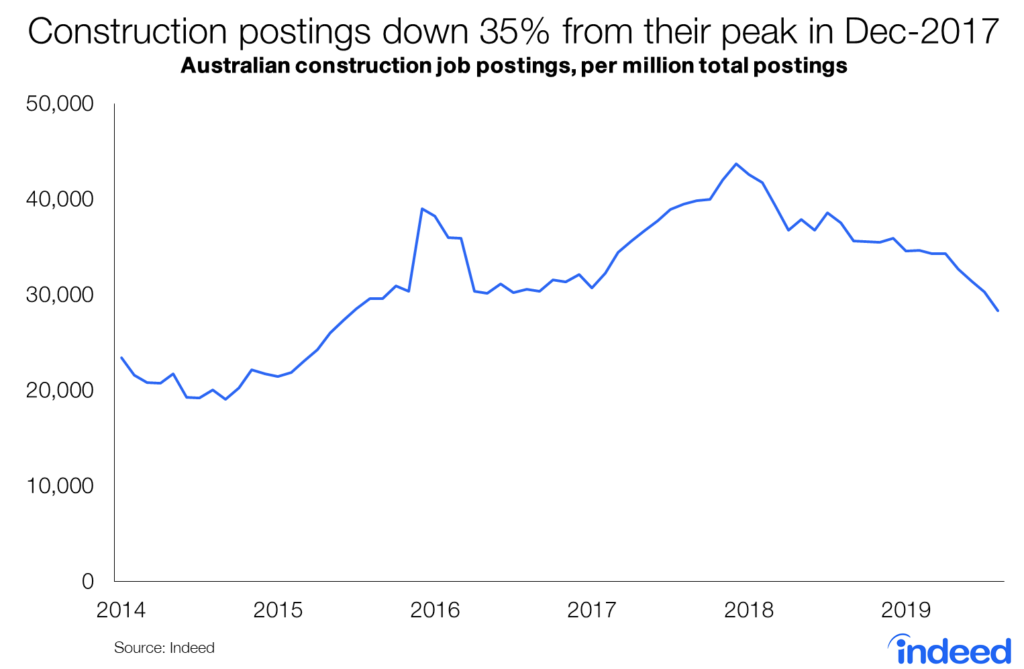

- Job postings in the construction sector have plummeted 35% since December 2017.

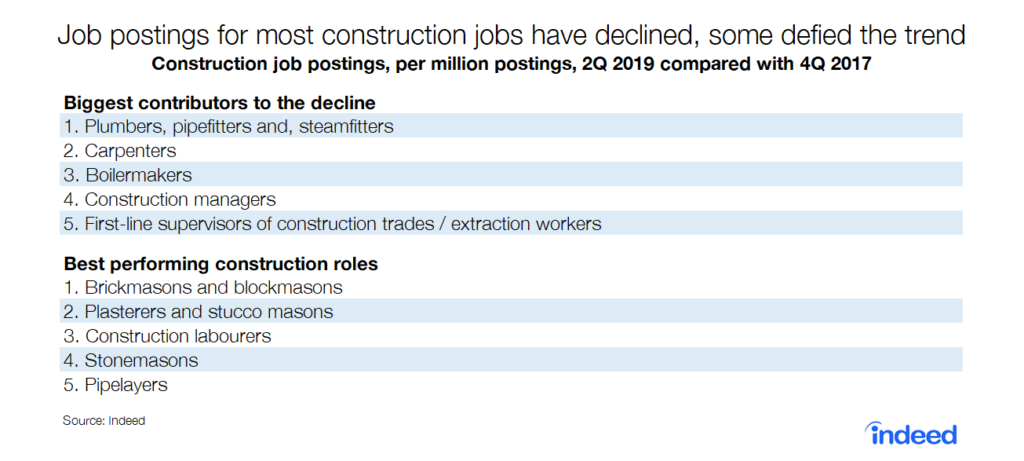

- Postings for 87% of construction occupations have declined since December 2017, especially for plumbers, pipefitters and steamfitters. But some occupations, such as brickmasons and blockmasons, have defied that trend, climbing over the past year-and-a-half.

- All is not lost — construction workers have a range of transferable skills. Jobs such as production painter and electrical engineer are popular among construction workers considering a career change.

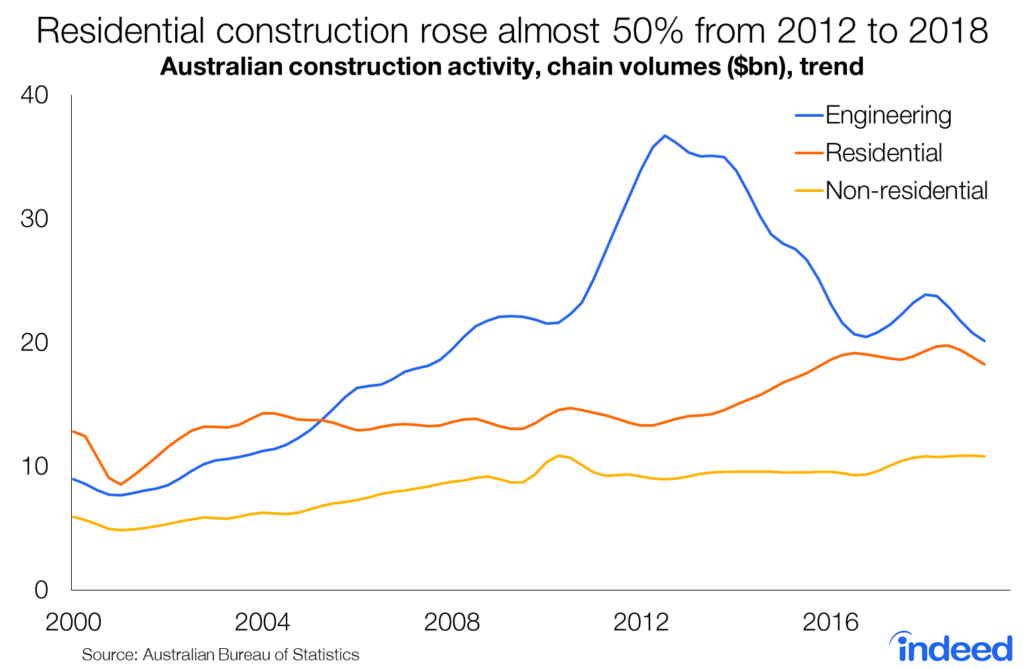

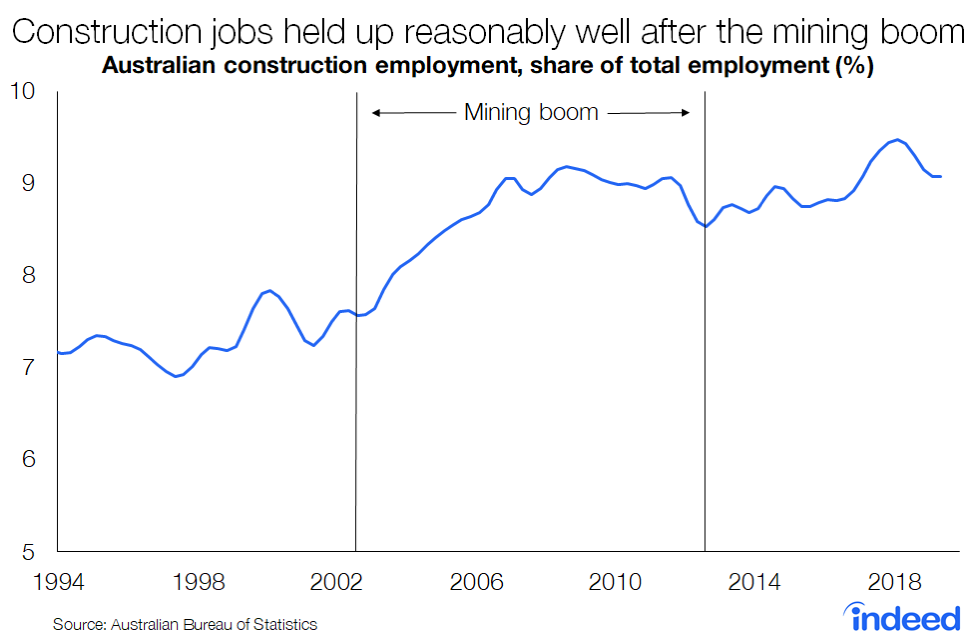

Australia’s construction sector has leapt from boom to boom over the past quarter century. Strong growth in residential construction around the turn of the century rolled into a once-in-a-lifetime mining investment boom. Over the past five years, residential construction has again expanded rapidly, supporting job creation. Consequently, construction peaked at 9.5% of Australian employment early last year, up from 7.2% a quarter century ago. Currently, construction stands at 9.1% of employment.

Our latest boom has now run its course and activity is expected to decline further over the next two years. Naturally, there is worry about construction workers. Indeed data suggests good reason for concern — the number of construction job postings per million postings was down 35% in August from its peak in December 2017. Construction employment topped out in February 2018, as a share of total employment, while construction activity began falling off a few months later.

Fortunately, construction workers possess a range of transferable skills, which may provide an outlet for those who aren’t able to find work in the sector.

Construction employment decline likely to continue

Construction employment appears likely to fall further as residential building projects are completed. While there are still plenty of projects in the pipeline, the number of new ones isn’t enough to offset those being completed. The declining demand for construction workers may explain why wage growth is lower in this sector than in most other Australian industries.

In the June quarter, just 13% of construction occupations experienced an increase in job postings compared with the December quarter of 2017. The jobs defying the downward trend include brickmasons and blockmasons, plasterers and construction labourers. Mining companies are performing well, benefiting from high prices for key commodities such as iron ore. Thus, new mining projects could provide an alternative for some displaced construction workers. The controversial Adani coal mine is an example of a mining project that could provide jobs for construction workers.

For most construction roles, opportunities have dried up — most notably for plumbers, pipefitters and steamfitters. Since the fourth quarter of 2017, postings for these occupations have fallen 23%, accounting for around a fifth of the total construction decline. Postings for carpenters and boilermakers were down almost 30%, making up another 22% of the decline.

Construction workers have benefited from a series of booms

Over the past quarter-century, several well-timed booms have supported construction employment. Residential construction activity, which measures homebuilding undertaken each quarter, rose around 80% from 1996 to 2004. Engineering construction, which primarily reflects the mining sector, surged 283% in a decade to a peak in September 2012. And then — almost on cue — residential construction came back to life, rising almost 50% from 2012 until topping out in 2018.

Residential construction is more labour-intensive than engineering construction, which means that a billion dollars of residential construction creates more jobs than a billion dollars of engineering construction. That’s likely why employment in the sector held up surprisingly well despite the extraordinary decline in engineering construction from 2012 to 2016.

Of course, as we contemplate a sizable fall in residential construction, the sector’s labour-intensiveness becomes a curse. The loss of jobs could be considerable and workers may struggle to find other jobs in construction.

Where to for construction workers?

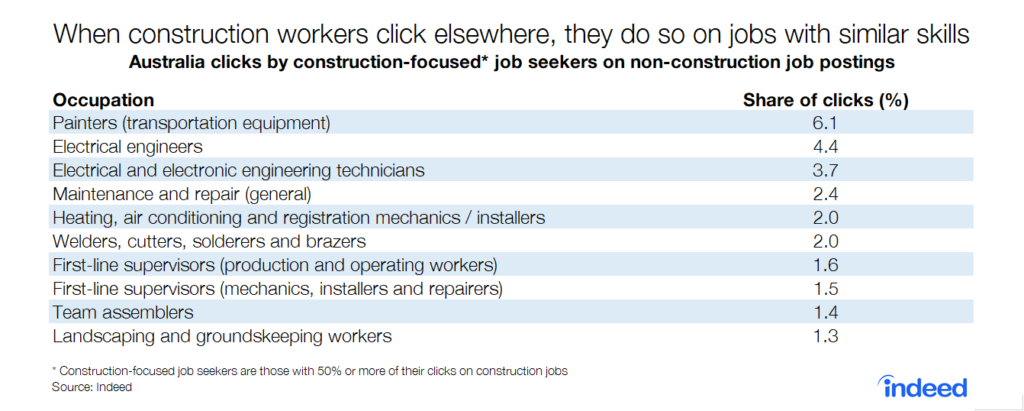

Analysis of clicks on Indeed shows what kinds of jobs construction workers are clicking on outside the sector. They often look for similar work in a new setting. For example, they may click on jobs in production, installation and maintenance, or architecture and engineering — all occupation groups that utilise construction skills.

In 2018-19, 6.1% of construction worker non-construction clicks were for jobs as painters of transportation equipment and 4.4% for electrical engineers. Many try to leverage their construction experience to find managerial roles. In fact, among job seekers with 50% or more of their clicks in construction, the ten most-clicked-on occupations outside the sector are mainly jobs in fields closely related to construction.

This highlights the transferability of skills across the construction sector. Workers often have options and may be able to move fluidly between sectors. If they can easily leave construction and find similar work elsewhere, then presumably they will be able to return easily when the sector begins expanding again. This places them in a favourable position even if construction opportunities keep on falling, provided that job opportunities in areas like production, maintenance or engineering don’t follow suit.

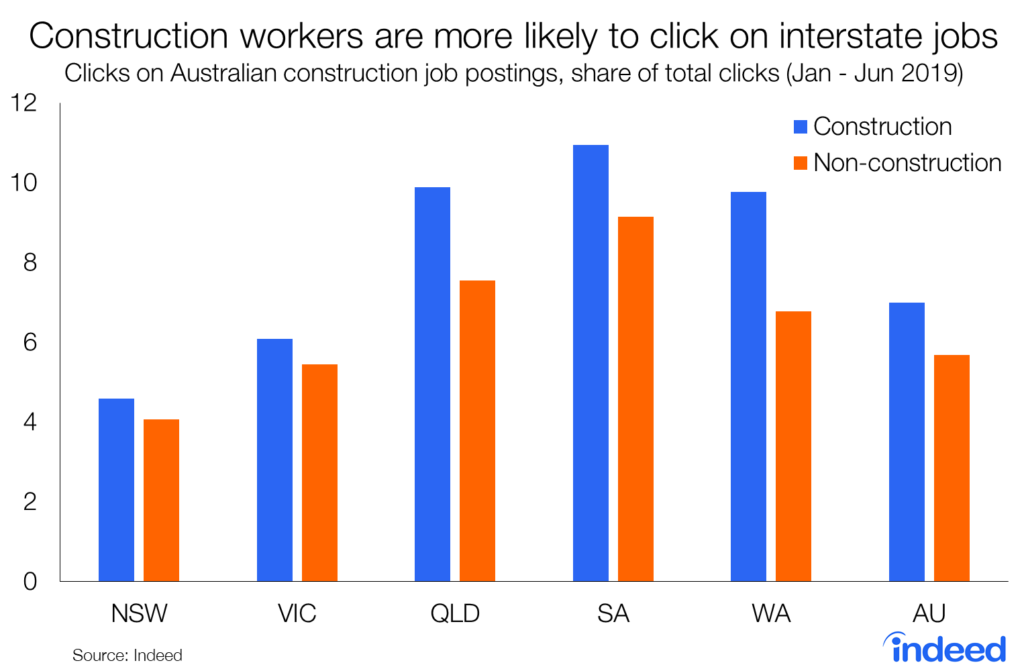

Compared with most job seekers, those in construction are more willing to search for work interstate. In the first half of 2019, 7.0% of clicks on construction jobs came from out-of-state job seekers — 23% higher than for non-construction job seekers.

In Western Australia and Queensland, those seeking construction jobs are 44% and 31% more likely than other job seekers to click on interstate jobs. That’s well above the 12-13% in New South Wales and Victoria, which may reflect the stronger jobs market in Australia’s two biggest cities. Sydney and Melbourne have led job creation in recent years, not just for construction but across the board, providing construction workers with a range of options.

The end of the residential construction boom means fewer opportunities for workers. And the long lead times for projects indicates that even big increases in the construction pipeline would take years to filter through to employment. Construction workers may need to consider alternative employment options, whether in different industries or different locations. Based on job seeker behaviour, production, maintenance and engineering appear the likely candidates, with mining another option if higher prices and favourable conditions lead to greater investment.