Since the UK voted to leave the European Union (EU) in June, the media spotlight has focused on the EU’s principle of freedom of movement and what it means for the countries that do or do not participate in it. Of course, the most obvious impact of a change in the EU-UK relationship aimed at lowering the levels of net inward EU migration—the scenario widely referred to as “hard Brexit”—would be to depress labour supply in the market.

This will have significant consequences. The positive contribution that EU immigrants have until now brought to the UK in terms of a boost to the labour supply is clear: not only are EU citizens more likely than other groups of migrants to move there in order to work, but once in the country they are more likely than natives to be in employment. Take that supply of labour away and the forecasts lean heavily towards the negative. For instance, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicts that Brexit-induced lower EU migration could cost the UK economy £6bn a year, and this would just be in terms of the direct impact of having fewer workers. Analysis by the IMF suggests that the impact of lower EU immigration on both growth and the public finances will be even more severe.

Of course, nobody can predict with certainty the outcomes of a “hard Brexit”. But employers need to prepare—and one potential source of data comes from job search trends. In this analysis we quantify the contribution brought by EU membership in terms of additional flows of actual and potential migrants, while controlling for the effect of other relevant characteristics. This will help us to answer the following questions: how relevant is the EU when it comes to the “virtual movement” of people across countries as captured by cross-border job search flows? And how relevant is it in comparison to other factors such as geography, language, culture and the overall attractiveness of a country? And what does this tell us about the likely fallout of a “hard Brexit”? Let’s take a look at the data.

EU membership and cross-border job search

In order to isolate the correlation between EU membership and cross-border job search we constructed a modelthat simultaneously controls for the impact of the characteristics of the sending and receiving countries (e.g. whether the country is particularly attractive or unattractive for job seekers), as well as for the impact of how close or distant they might be in terms of both geography and language/culture.

All these factors taken together are expected to determine the likelihood of a job seeker to search for a job in a different country based on where he or she is currently located. We can think of EU membership as another factor contributing to the reduction of the legal and bureaucratic costs of moving for potential migrants and which affects their considerations regarding whether to take up a job in another EU country or not. Using a dataset of cross-border job search flows on Indeed across 49 countries (that includes both EU and non-EU countries) in an average month in 2016, we estimated the amount of additional job search that takes place within the EU, where free movement of labour is a reality.

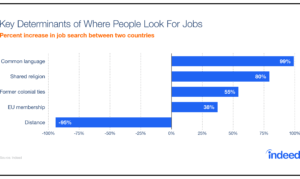

As the chart above makes clear, our analysis shows that language is the most significant determinant of the amount of job search exchanged between two countries: those that share a common tongue exchange 99% more searches, controlling for the other determinants.

Distance between the sending and receiving country has a similar effect, but opposite in terms of direction. For each one hundred percent increase in our measure of distance, the two countries are expected to see their job search exchange decrease by 95%.

The effect of having cultural ties and similarities in the legal or bureaucratic system (which our model measures as the presence of historical colonial links and a common religion) is somewhat smaller, but still very relevant. Countries that share a religion exchange on average 80% more job seekers, while countries that were formerly part of the same colonial empire show, on average, a 55% increase in their bilateral flows of job search.

Meanwhile, membership of the EU delivers an additional 38% increase in the relative amount of job search exchanged between two member countries in an average month. But while this may be the smallest effect among the ones we estimated, it does not mean that belonging to the EU is an insignificant factor when it comes to cross-border job search, and not just because this number is equivalent to tens of thousand of unique searches each month. Even once we factor out all the possible factors that influence the likelihood of a job seeker to search for work in a specific foreign country (including EU ones), EU job seekers are still significantly more likely to search within the EU borders.

Thus the average international job seeker who is looking for a job on indeed.co.uk is 38% more likely to be based in another EU country, and this effect remains even after we control for a range of relevant determinants, such as coming from another English-speaking country or from a territory that used to be part of the British Empire, all of which also have a strong net positive effect.

Cross-border job search vs migration

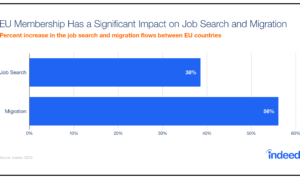

Of course, cross-border job search does not equal migration. However, when we ran the same model in order to explain the direction of migration flows, as measured by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) we found that all the relevant effects remain consistent. This time, however, EU membership is associated, on average, with a 56% additional increase in migration flows exchanged among member countries.

This is slightly higher than the 38% average increase we estimated for job search, but fairly close. This difference is likely caused by the fact that potential bureaucratic and legal costs are obviously more relevant for actual migrants than for job seekers who may only be considering a move to a different country. If we consider that the biggest effect of EU membership is to virtually eliminate these costs, then it is not surprising to see that the effect is larger for actual migrants rather than virtual ones.

More generally, this means that international job search is affected by the same factors that affect migration or, to put it another way, tracking where people search for jobs can give us a unique glimpse into potential migration patterns—something that is even more relevant if we consider how hard it is to come by up-to-date information on migration flows.

This is especially valuable as even the most comprehensive data on global migration, such as those collected by the OECD, date back to 2010. Meanwhile there is a growing concern that more up-to-date national migration figures, including those collected by the UK’s Office for National Statistics, may not be very reliable. Search data can thus provide an alternative, real time source of data on migration intentions.

Thus, even though UK-based job search directed to the EU is about one-half of the EU-based traffic directed to UK, both flows are significant in terms of magnitude. This suggests that possible extreme measures aimed at curbing EU immigration—widely anticipated in the different scenarios of “hard Brexit”—would put the British labor market at risk of losing as much as 38% of interest from job seekers located in other EU countries. This would ultimately translate into lower levels of migration as well.

What does this mean for post-Brexit UK and EU labour markets?

Previous Hiring Lab research showed not only that the UK has been a net talent attractor from the EU, but that it is also by far the most popular destination for job seekers located in other EU countries. In recent years, the British labour market has been able to attract and rely on a steady flow of jobseekers and workers coming from other EU countries to fill job vacancies in the UK.

Over the last decade there has been a 123% increase in the number of people working in the UK who were born in other EU countries and—as a result—the EU now accounts for 41% of all foreign-born workers, up from 31% in 2005. According to 2015 data from the Annual Population Survey (APS), the majority of EU-born UK residents (54.8%) listed “employment” as the main reason for their move. Compared to non-EU migrants, they are 180% more likely to come for employment-related reasons and 30% less likely to join or accompany a family member. Research published by Oxford Economics earlier this year showed that in Q4 2015 the employment rate for those born elsewhere in the EU and living in the UK was 70%—well above the equivalent rates for those born in the UK and in non-EU countries (both 60%).

Official data show that these individuals tend to be younger and are more likely to be in work than British citizens. Indeed data also show that they are more likely to be interested in higher skilled technical positions that firms often struggle to fill. Thus employers based in the UK that have been relying on a steady stream of EU workers will suddenly have to find alternative sources to fill tens of thousands of vacancies each month.

While some up-skilling or re-skilling of the local workforce might take place, in the short to medium run it is likely that the shortfall of EU candidates will intensify hiring difficulties with negative consequences for businesses and the British economy. Similarly, the door to other EU labour markets will be shut for the thousands of job seekers located in the UK who search for jobs on the continent every day.

Link to Methodology

- Our sample only includes 19 EU countries with an Indeed website.

- Several studies have used the same approach to predict flows of people across countries. See among others: Beine, Michel, Frédéric Docquier, and Çağlar Özden. “Diasporas.” Journal of Development Economics, Symposium on Globalization and Brain Drain, 95, no. 1 (May 2011): 30–41. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2009.11.004.

- Our model is not immune to the classic “chicken or the egg problem”—that is whether the higher flows of workers and job seekers across EU countries is a consequence of the EU membership or if these flows have always been higher among countries that today belong to the EU.

- Data refers to 2010 and and has a smaller sample. In the migration sample EU flows (those between member countries) make up 20.9% of the sample Vs 14.6% in the job search one.

- Oxford Economics analysis.