From builders and butchers to dentists and au pairs, many jobs in Britain are carried out by people from the European Union. However, as migration falls in the run-up to Brexit and uncertainty about the future openness of Britain’s labour market rises, there are fears of skill shortages in key areas of the economy. Are those fears justified? How interested are European jobseekers in British jobs? And which sectors are most vulnerable to the departure of those Europeans who are already here?

Indeed job search patterns are well-suited for answering these questions. International job search traffic reflects migration flows and serves as a real-time indicator of interest in specific jobs and regions. By looking at the activity of visitors to Indeed’s UK site, we can paint a detailed picture of the potential supply of international workers to Britain’s tight labour market.

That picture is one of a general decline in European jobseeker interest in British jobs. Among the areas of the economy that particularly rely on people from the EU, healthcare and construction stand out as most exposed to a potential worker “Brexodus”. At the same time though, Europeans looking for jobs that involve technology, finance and language skills have not been put off by Brexit just yet. This suggests that Britain could keep its position as a global tech and banking magnet in a post-Brexit world, provided that migration policy is sufficiently flexible to accommodate an internationally mobile workforce.

European jobseekers are losing interest in British jobs

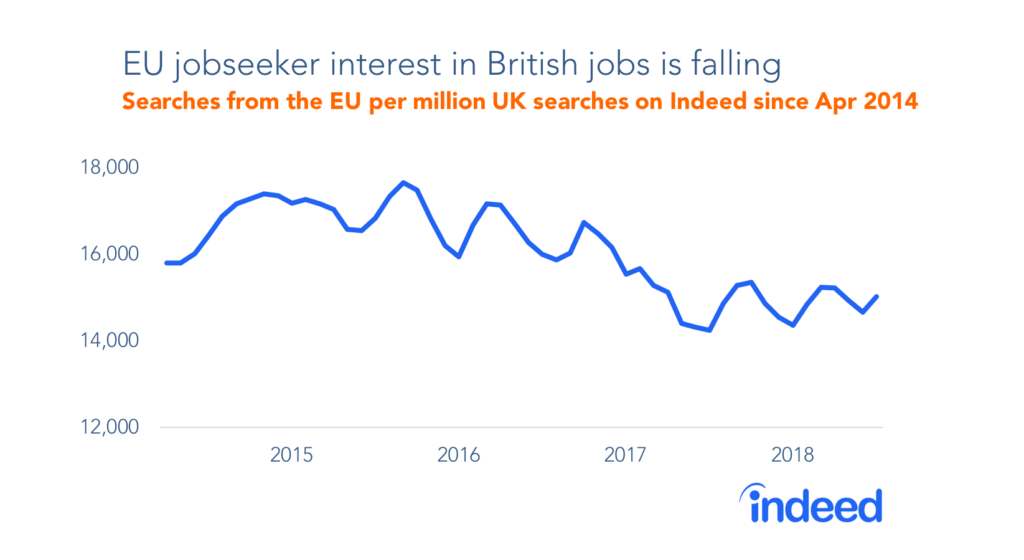

We begin by looking at job searches from EU countries as a share of all activity on Indeed’s UK site as a way to measure the relative contribution of European jobseekers. The trend shows a decline, suggesting that European interest in working in Britain is waning. More surprising is that this fall-off started well before the June 2016 Brexit referendum.

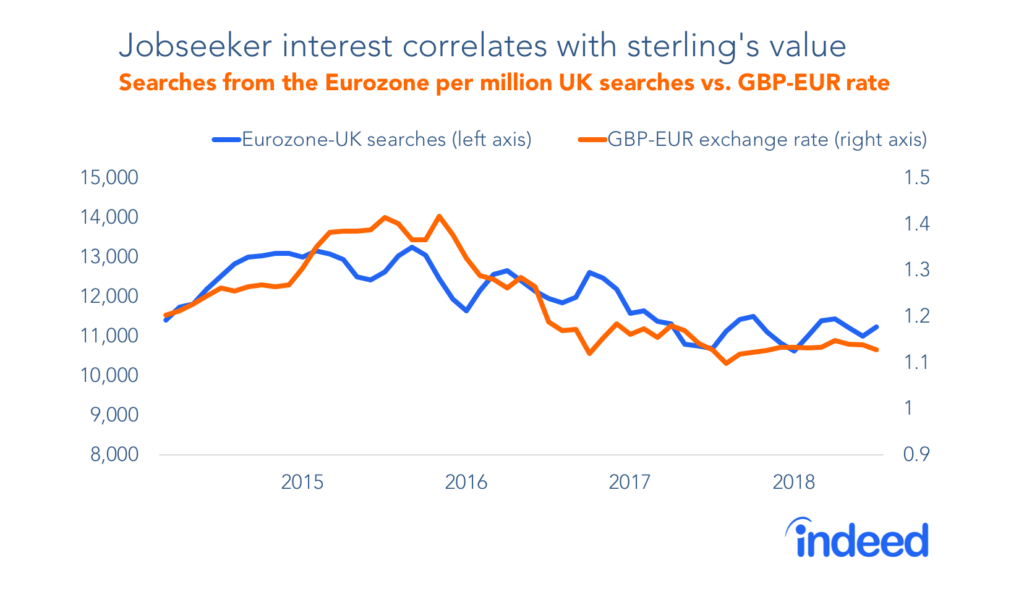

The downward trend in searches coincides with persistent weakness of the pound relative to the euro and other European currencies since mid-2015. A weaker pound makes Britain a less attractive destination to work in, particularly for people keen to translate their earnings into purchasing power back home. This happened at a time when labour markets in many European countries were strengthening, reducing the incentive to move abroad. More recently, the weakness of the pound has once again come to the fore in the context of “no deal” Brexit and its potential impact on the sterling.

Another way to see the decline in European jobseeker interest is to measure searches for British jobs relative to all EU cross-border searches. Britain’s share of those searches has fallen, meaning that those Europeans who search for jobs abroad increasingly are finding other destinations more appealing.

Which areas of the economy are most vulnerable to a “Brexodus”?

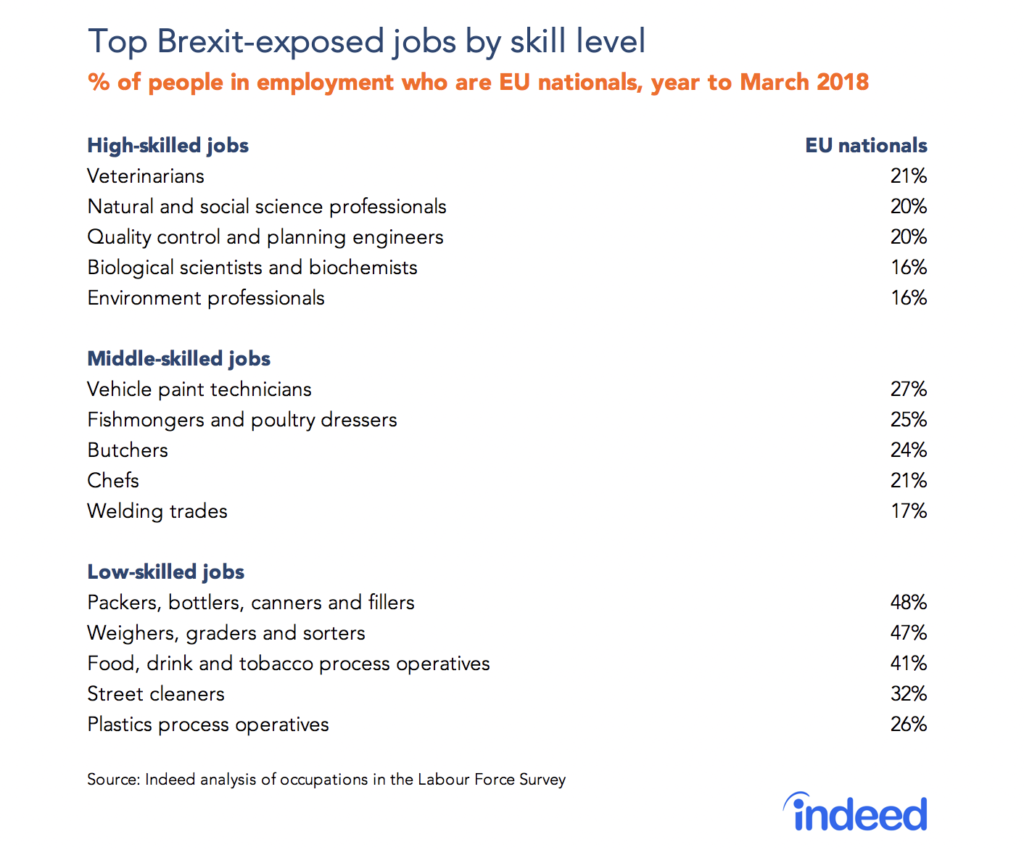

We compiled a list of jobs where EU nationals currently represent the highest proportion of the workforce, based on the Labour Force Survey. These “Brexit-exposed” jobs are spread across low-, middle- and high-skilled professions, and across many areas of the economy.

Veterinarians top the list of high-skilled jobs, followed by scientists, quality control engineers and environment professionals. Professions outside the top five include architectural and town planning technicians (15%), architects (14%) and dentists (14%).

Vehicle paint technicians come first in the ranking of Brexit-exposed medium-skilled jobs, indicative of the high proportion of Europeans in the automotive industry. Food-related professions like fishmongers and poultry dressers, butchers and chefs also make the list, as do welders. Outside the top five are bakers and flour confectioners (16%); construction and building trades (16%); and painters and decorators (16%).

Food is also prominent on the low-skilled end of the job spectrum, which features jobs related to packaging, sorting and processing food products. Outside the top five are housekeepers (26%); forklift truck drivers (26%); launderers, dry cleaners and pressers (22%); vehicle valeters and cleaners (22%); and childminders (21%).

The risks Brexit poses to trade in goods have received prominent attention — and it has even been said that trade barriers may lead Britain to run out of sandwiches! The table shows that disruptions to the flow of people may not only interrupt lunch, but also disturb the smooth running of the labour market. Sectors that deal with key areas of everyday life, like food production and service, housing, health and childcare, could be disrupted by a “Brexodus” of European workers.

Will Britain run out of builders, butchers, dentists and au pairs?

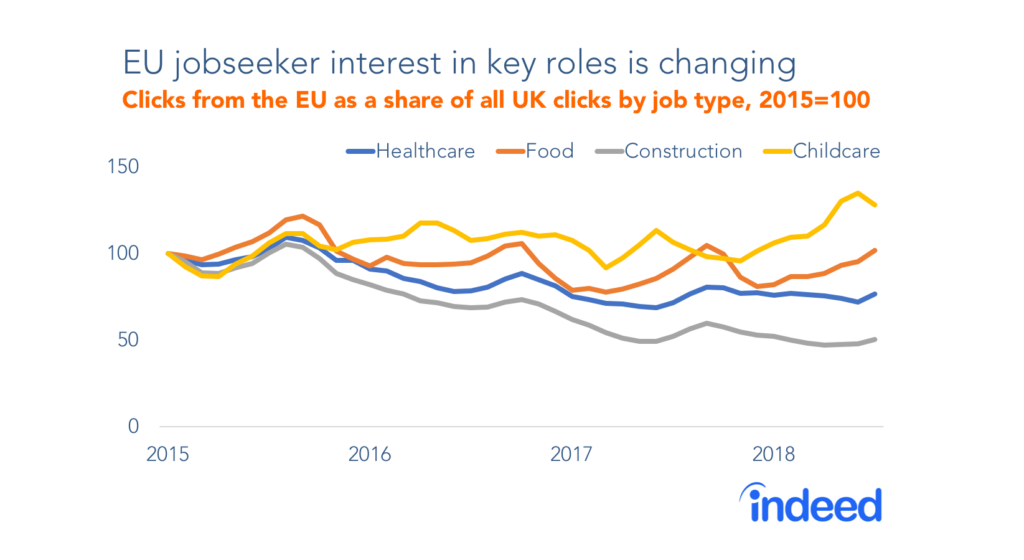

Many of the jobs that rely heavily on EU nationals fall into four broad categories: food, housing, health and childcare. We therefore looked more closely at the interest of European jobseekers in those areas as expressed by clicks on specific jobs advertised on Indeed. To account for growth in overall job search activity over time, we report clicks by European jobseekers as a share of all clicks on British jobs.

Against the backdrop of Brexit and a falling sterling, clicks on childcare jobs surged 49% in the three years since April 2015, just before the general election that enshrined a commitment to a referendum on EU membership in the government programme. We calculate the change to April 2018 to remove seasonality effects. Clicks on food jobs, which include both food production and service, remained broadly stable compared with other categories, growing 1%. In contrast, interest in healthcare and construction jobs dropped 21% and 42% respectively.

Why do the trends for food and childcare differ from those for healthcare and construction? It could be that jobs in these sectors attract people with different characteristics. Looking at the top countries of origin for each job category hints at this as a possible explanation.

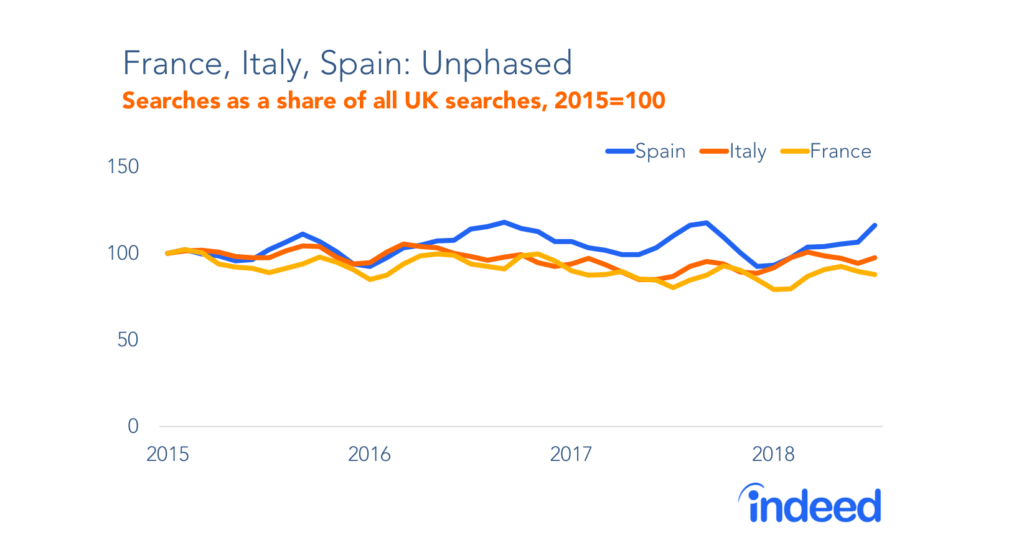

The top source of clicks on food and childcare in 2018 is Italy, followed by Spain and France. Jobseekers from those countries have maintained a constant overall interest in British jobs since before the Brexit referendum. One reason might be the weakness of the domestic labour markets in those countries relative to Britain. The surge in childcare interest could also be driven by booming British demand for early education.

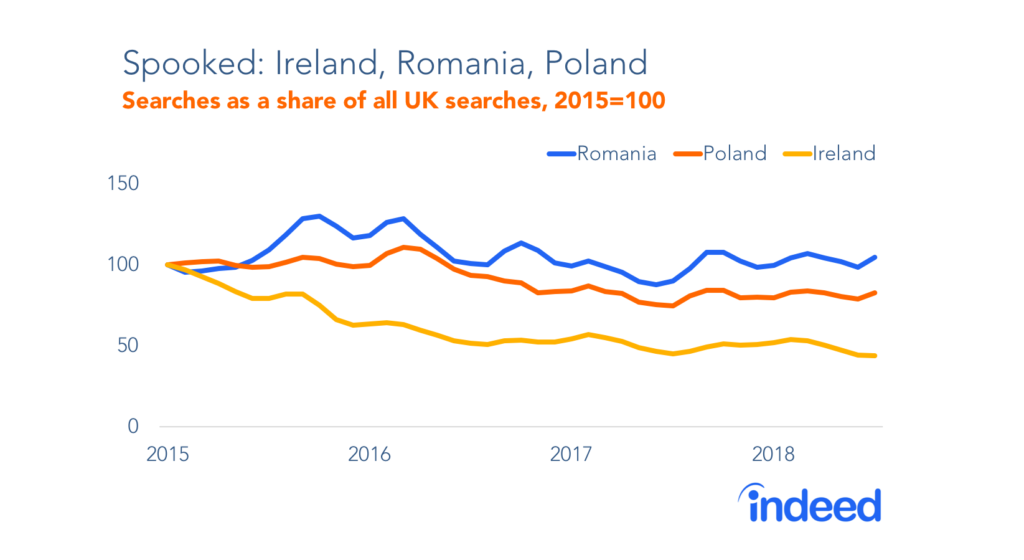

In contrast, construction attracts most attention from jobseekers in Ireland, Romania and Poland. Ireland is also the top origin of clicks on healthcare jobs, followed by Spain and Italy, with Romania a close fourth.

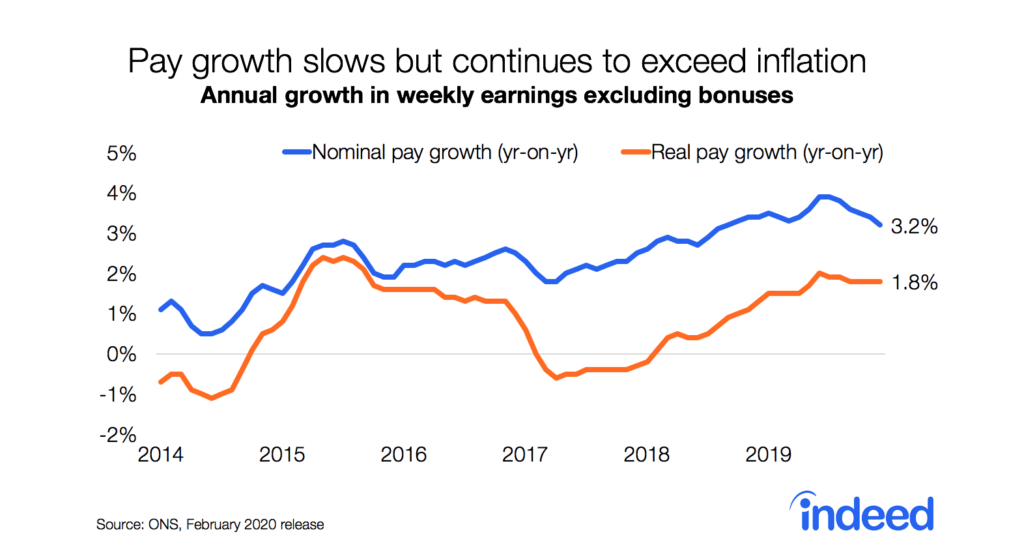

Interest from Ireland, Romania and Poland in British jobs diminished in the three years up to April 2018 relative to the interest of people from other countries. Irish jobseekers’ share of searches declined 44%, while the Polish share fell 26%. Interest from Romanian jobseekers was still rising in 2015, as restrictions on their ability to move to Britain had only recently been relaxed. But Romania’s share of clicks fell 19% in the two years following its January 2016 peak. In all three countries, the domestic labour market strengthened over this period, with unemployment falling and wages rising faster than in Britain — reducing incentives to move abroad and perhaps contributing to falling interest in British jobs.

Does declining European jobseeker interest in healthcare and construction raise concerns about worker shortages? Looking at employer demand, healthcare job postings have been stable and construction job postings have risen as a share of all postings on Indeed — a telltale sign of sustained demand for workers. Therefore, overall, the widely aired concerns about post-Brexit skill shortages in healthcare and construction may not be entirely misplaced.

What next for Britain’s international workforce?

Britain has a truly international workforce, with people from Europe working in a wide range of roles, including jobs outside food, construction, health and childcare. Consequently, for this post, we looked more broadly at all the jobs Europeans click on when searching on Indeed. Our analysis shows that positions involving language translation, finance, technology and research are among the top jobs favoured by European jobseekers relative to their British counterparts. These preferences have not changed since 2015. It appears that many high-skilled European jobseekers have not been put off by Brexit just yet.

Will Europeans working in Britain suddenly up sticks and leave after Brexit? Much will depend on the details of the final deal with the EU and the resulting migration framework. The impact of Brexit on the economy and on the pound will also likely be among the determining factors. In the meantime, uncertainty about future migration policy and the spectre of a no-deal scenario have already prompted many employers to voice concerns about their ability to recruit and retain European workers.

Job search patterns on Indeed suggest that European jobseekers are turning their back on jobs related to healthcare and construction. Nursing and the skilled trades are precisely some of the occupations where the educational system has often been blamed for chronically undersupplying professionals. Therefore, as Brexit looms closer, a key challenge for policymakers will be to design a training and migration framework flexible enough to supply the skills the economy demands.

———————————————————-

Methodology

We examined the search behaviour of Indeed jobseekers from April 2014 to July 2018. We define a cross-border search as one in which the country of the user’s IP address differs from the country of the Indeed site used for the search. Plots are based on three-month moving averages. Percentage changes over the past three years, referenced in the text, relate to the period from April 2015, the month before that year’s general election, to April 2018 to remove seasonality effects.

We use “EU” and “Europe” as shorthand for all countries whose citizens benefit from the European Union’s freedom of movement rules and therefore have the right to move to the UK for work. This includes Switzerland and countries in the European Economic Area that are not part of the EU, such as Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein.

Our analysis of the correlation between the euro-sterling exchange rate and job search patterns considers the subset of EU countries that used the euro during the entire period of our study: Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain. We also include Bulgaria, as its currency is linked to the euro. We use monthly average exchange rates provided by the Bank of England.

The ranking of Brexit-exposed jobs is based on the ONS Labour Force Survey. It focuses on occupations with at least 10,000 EU nationals working in Britain. Skill levels are defined using the SOC 2010 occupational hierarchy.