Is there anyone left to hire in the UK?

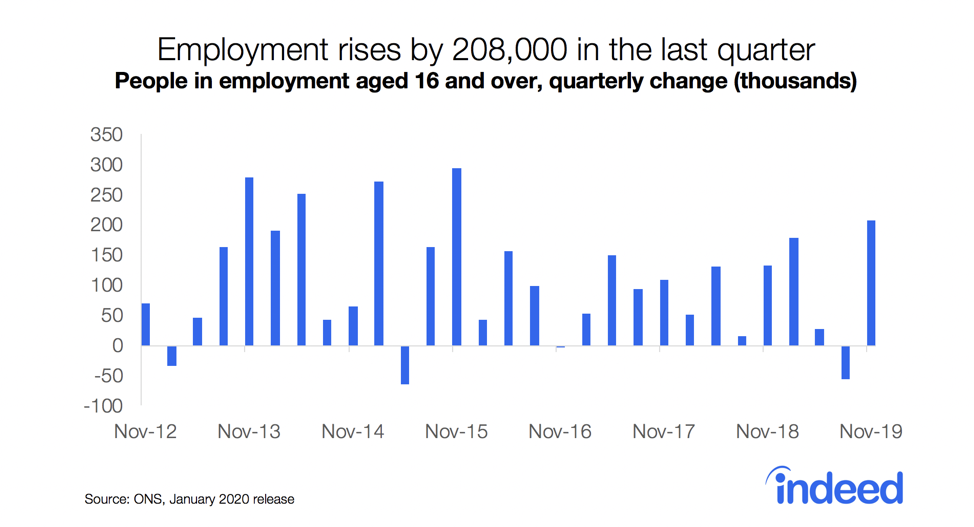

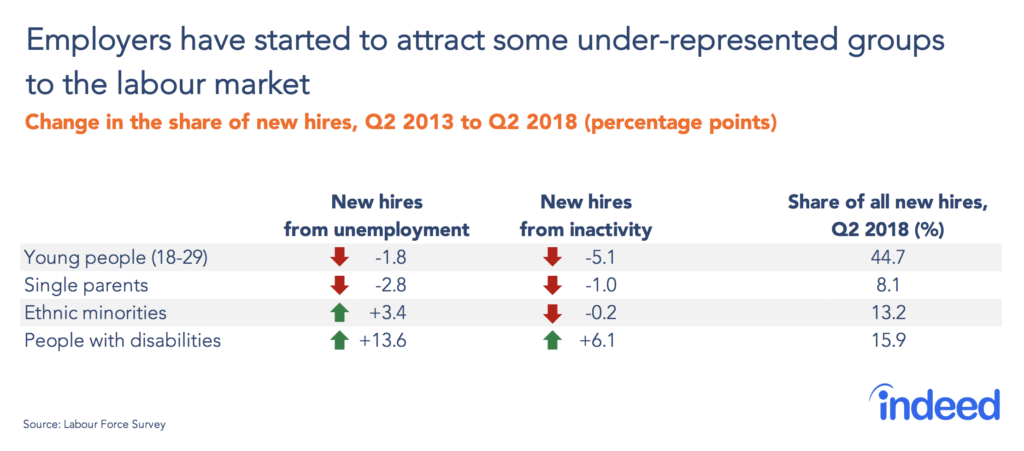

The economy hovers around full employment and the number of unfilled job vacancies has reached a record 845,000. Nevertheless, there are still groups of workers that employers have not fully tapped. In tight labour markets, employers tend to increase hiring from groups that find it harder to land a job or are under-represented in the labour market. For instance, over the past five years, as the pool of unemployed people has shrunk, ethnic minorities and people with disabilities have accounted for a rising share of new hires. Food and beverage service, healthcare and IT have increased hiring of minorities most, while retail, cleaning, and food and beverage service have hired more people with disabilities.

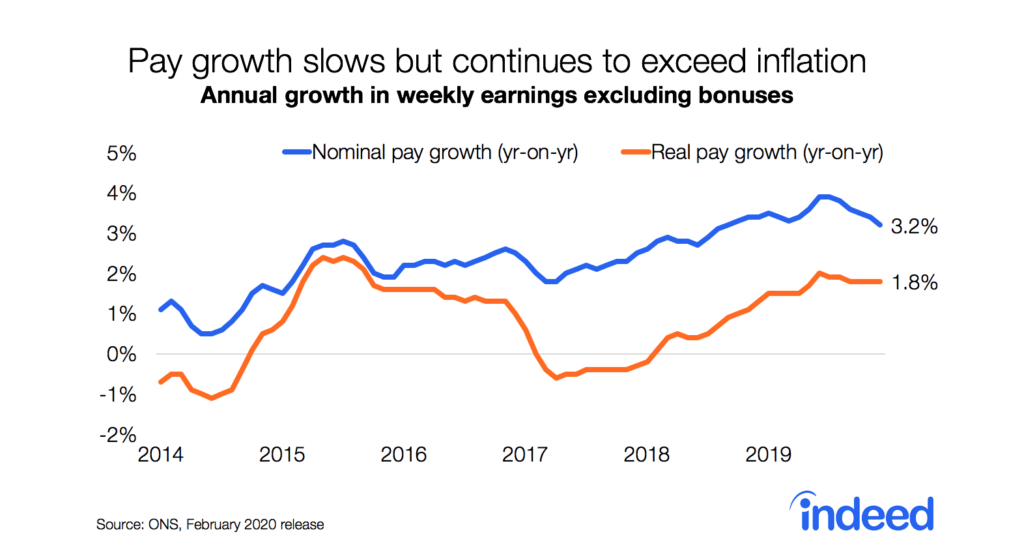

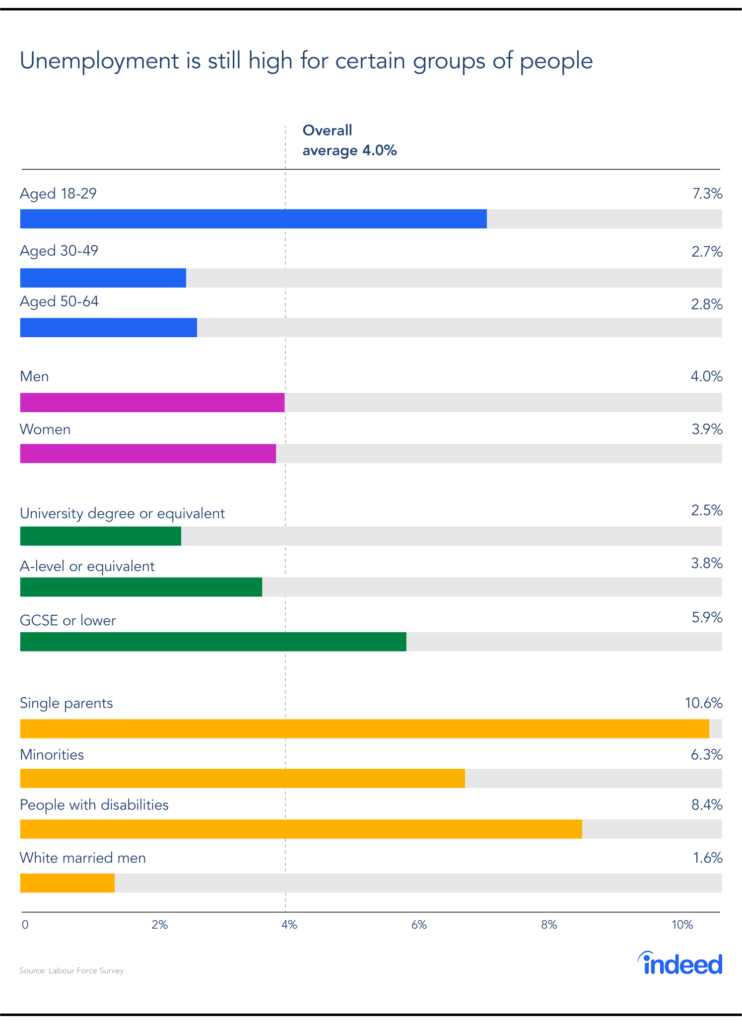

Yet employers can still do more. In addition to minorities and people with disabilities, young people, those with low education levels and single parents also experience much higher than average unemployment rates. Those demographic groups represent an opportunity for businesses. One reason why looking at them might be attractive to employers is that wage growth for people moving from one job to another has accelerated, and that could make hiring people already in work more expensive.

Low unemployment and falling numbers of European workers following the Brexit vote mean that no employer can afford to ignore people available for work in today’s competitive labour market. Data suggest three strategies for employers:

- First, search broadly and tap into the full diversity of the workforce to address the ebbing flow of new entrants into the labour market, including migrants.

- Second, invest in training to make new hires productive fast, since many of the people who do not already have a job and are available for work may lack relevant skills or experience.

- Third, invest in retention by raising pay or improving other aspects of the job, like career progression, to hold existing staff and minimise the need for replacements.

Is the labour market tight for everyone?

Overall the UK average unemployment rate was 4.0% in the second quarter of 2018, but the rate was not uniformly low for all demographic groups. Among those with substantially higher unemployment rates were people aged 18 to 29 (7.3%), those with no formal qualifications higher than GCSE level (5.9%), single parents (10.6%), ethnic minorities (6.3%) and people with disabilities (8.4%). Unemployment rates have declined for those groups since the last recession, but remain high relative to other groups in the workforce.

Of course, those groups sometimes overlap. For example, young people with a minority background have a 10.6% unemployment rate, similar to that of single parents, and almost 4 percentage points higher than nonminorities in the same age group.

Measures other than unemployment also indicate that these demographic groups are underutilised. For example, minorities and people with low qualifications have above-average rates of inactivity and are more likely to be stuck in part-time jobs because they cannot find full-time work.

Are employers tapping into underutilised demographic groups?

To see whether employers have increased hiring from the demographic groups with the highest unemployment rates, we looked at how the composition of new hires has changed in the past five years. The groups that increased their proportion of new hires from unemployment most are people with disabilities, whose share grew 13.6 percentage points to 20.9%. They are followed by ethnic minorities, whose share increased 3.4 percentage points to 14.9%. Retail, cleaning, and food and beverage service gained most in share of new hires of people with disabilities. In hiring of minorities, food and beverage service, healthcare and IT increased their share most.

At the same time, single parents and young people have lost share among new hires from unemployment despite high joblessness among those groups today. There are several possible explanations. Employers may find it more costly to hire from these groups due to the extra pay, benefits or training they may require. Job preferences may also play a role. For instance, young people’s job aspirations do not always match the jobs that are on offer, which might make attracting them to certain occupations difficult.

What should employers do to fill the record number of job openings?

Employers struggling to find recruits might consider looking for new hires in new places. Searching broadly across demographic groups can offset pressures from the fall in the number of European workers in the UK. While employers have increased hiring from some underutilised domestic groups, unemployment rates for all those groups are still high. These represent areas of hiring opportunity.

Many people in these demographic groups face barriers that make their job searches difficult. For instance, navigating the job market and finding a match with the right employer may take longer for young people entering the labour market for the first time. Single parents are likely to face challenges because of inflexible schedules, long commuting distances and availability of childcare. People with certain disabilities, such as mobility restrictions, will also be limited to jobs they are capable of performing with appropriate adjustments.

Employers who want to tap into these groups may need to help candidates overcome those obstacles. For example, attracting single parents may require allowing more flexible schedules, putting in place ‘returnships’ to help people transition into work after a career break or providing childcare benefits above the government allowance. Employing disabled workers may require workplace adjustments, such as accessibility renovations.

Of course, these actions often carry a cost. But employers struggling to hire in today’s market might find them worth considering despite the expense. For instance, jobseeker interest in flexibility has grown substantially in recent years. Searches for working from home or flexible or remote work are up 71% as a share of all searches on Indeed’s UK site since 2015.

Hiring people with limited experience or those who have been out of the labour market for some time may also require an investment in training. Since such training can be costly and the investment is lost if employees leave, employers have incentive to retain staff by raising pay or modifying the workplace in ways that employees value. Some economic models predict that such actions may, under certain circumstances, induce greater effort from employees, which might allow employers to recoup part of the costs in the form of higher productivity.

Methodology

For this analysis, we used Labour Force Survey data from the second quarter of 2013 and 2018. We define new hires as individuals who have been continuously employed for less than three months in their current job when they are observed in the longitudinal Labour Force Survey. We define new hires from employment as people who were in employment in two consecutive quarters but were reported being continuously employed for less than three months when observed in the second quarter, following the methodology used by the Office for National Statistics. New hires from unemployment and inactivity are defined similarly.

Single parents are defined as people who are not married, cohabiting or in a civil partnership and who live in a lone-parent household with a dependent child. Ethnic minorities are defined as individuals coded as nonwhite in the survey. People with disabilities are defined as those who are disabled under the Equalities Act. All data are for employees aged 16 or over, except for data that relate to specific age groups.