Key Points

- Resurgent labour demand continues to outstrip worker supply.

- Candidate interest in lower-paid sectors has tightened substantially.

- Jobseekers have plenty of choices, though Great Resignation talk appears overblown.

- Inflation is pressuring real wages, but it’s not yet clear whether pay growth will broaden in response.

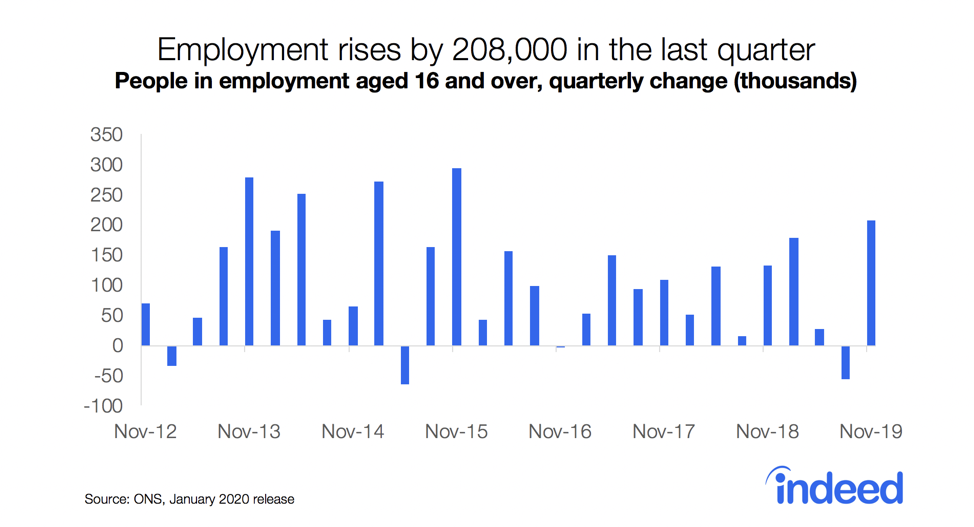

The UK labour market has staged an impressive comeback from the pandemic in 2021. Not only has unemployment stayed low, largely thanks to the furlough scheme, but demand for new workers has roared back to break new records in recent months. Rather than the previously feared spike in unemployment, as we head towards the end of the year the labour market is the tightest it’s been in decades. The pressing issue instead is worker shortages.

This is particularly true in reopened sectors that have been hiring in large volumes for months and where job postings are furthest above pre-pandemic levels. These are predominantly in-person, lower-paid sectors, and demand for staff in them has outpaced the supply of workers.

Nonetheless, the labour market’s recovery is incomplete. Employment is still more than half a million below its pre-pandemic level, largely reflecting a big decline in self-employment. The number of economically inactive people — those neither working nor actively seeking employment — is also over half a million higher than on the eve of the crisis. What’s more, Brexit has curtailed the UK’s ability to easily fill gaps with workers from EU countries. What it means is that the number of UK workers participating in the labour force needs to increase substantially if we are to keep persistent worker shortages from stalling the recovery.

Hopefully, labour market momentum will continue heading into 2022, providing yet more opportunities and pulling more people into the workforce from the sidelines. That would allow both businesses and the economy at large to continue recovering. However, the pandemic continues to cast a shadow of uncertainty, with new variants or waves of the virus presenting downside risks.

Jobseeker interest is shifting

Changes in relative jobseeker interest over the pandemic illustrate the extent to which candidate availability has tightened in lower-paid sectors. Conversely, higher-paid categories have become relatively more popular with jobseekers.

To find out which jobs workers are looking at, the Indeed Hiring Lab has developed a metric we call relative jobseeker interest. This measure captures changes in jobseeker interest in an occupational category since the beginning of the pandemic compared with the average job. Our pre-pandemic baseline is 1 February, 2020. A positive change in this metric since then means the occupation has become more attractive to jobseekers than before the pandemic compared with the average posting.

In general, the biggest falls in relative jobseeker interest have been in lower-paid sectors that recently have grown strongly, like cleaning, warehousing, construction and hospitality. Much of the declines in these areas happened after the reopening roadmap was announced on 22 February, 2021. Falling relative jobseeker interest indicates the supply of workers has not kept pace with resurgent demand. More broadly, Hiring Lab surveys find job search lacks urgency for many workers. Even those currently out-of-work are in little hurry to find new jobs. Survey respondents continue to cite financial cushions, caring responsibilities and health concerns related to COVID-19 as factors holding back search.

Meanwhile, the relative interest metric shows a shift toward higher-paid categories like legal, tech and healthcare. That’s due partly to the fact that job posting growth in these sectors hasn’t been as spectacular as in many lower-paid occupations. Outside of frontline healthcare, many of these are job categories where working during the pandemic has been relatively safe and comfortable, and in which remote work is more feasible.

Raising wages and offering hiring incentives may be one way for employers in lower-paid sectors to bring in staff. But it may not be enough on its own. It may also be necessary to improve working conditions and offer greater job flexibility to draw more people back into the labour market, including older workers, disabled people and parents.

The recently announced 6.6% increase in the national living wage and 4.2% increase in the voluntary living wage are good news for workers in lower-paid sectors. At the same time though, a spike in inflation driven by energy prices means many workers aren’t gaining purchasing power and are probably not feeling a lot better off.

Though a few specific sectors with particularly acute worker shortages are registering strong wage growth, pay is not growing much in other low-paid sectors. In these, higher pay relies on minimum wage increases.

Is there really a Great Resignation?

There’s been much talk about what’s been dubbed a Great Resignation. In the UK as well as other countries, people are said to have reassessed their priorities during the pandemic, with many leaving their occupations to find something different. But do the data really support this?

The latest ONS Labour Force Survey (LFS) shows that both resignations and job-to-job moves jumped by a third in the third quarter of 2021, reaching their highest levels since current records began 20 years ago. Nearly a million people moved between jobs during the third quarter, with 391,000 of these switches following resignations, a 38% share.

At that level, resignations as a share of job-to-job moves are not at historically high levels. What appears to be happening is not a mass reassessment of priorities. Rather, voluntary job moves are ratcheting up as labour demand bounces back, giving people more options. Meanwhile, job switches postponed during the pandemic have finally had chances to take place.

LFS data indicate 57% of job moves in the third quarter of 2021 were within the same industry, a higher proportion than the 53% during the same quarter in 2019. That does not support the hypothesis that people are increasingly moving to new, supposedly more gratifying pastures. High-skilled workers account for the largest number of moves in absolute terms. But most of the third-quarter jump in job-to-job moves was driven by low-skilled and medium-skilled workers. High vacancies, as well as rising pay in some sectors, has given them greater opportunity and incentive to move, perhaps for better wages or working conditions. That in itself doesn’t imply a reassessment of priorities.

Our October job search survey showed a range of factors was motivating people to look for new positions, with higher pay cited by 44% of respondents, the most frequently reported reason. Given high inflation, pay might become even more important in 2022. Changes of career path, better benefits and more flexibility were also popular factors motivating people to search.

Labour market trends to watch in 2022

The labour market appears to have taken the end of the furlough scheme in its stride. That means tight labour market conditions and hiring difficulties for employers look set to continue into the new year.

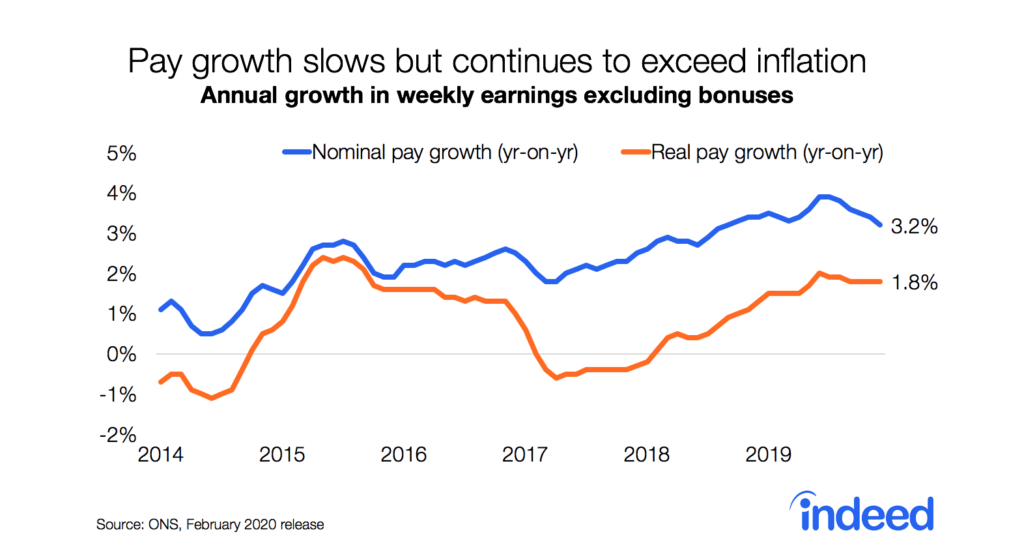

A key question is whether this tight labour market will translate into a broadening of pay growth across the labour market. With consumer price inflation expected to peak in the region of 5% over coming months, real pay growth could very well go negative for the third time in a decade. That gives workers whose skills are in demand every incentive to push for pay increases.

Monetary policymakers are closely watching for any signs that pay growth is rising to a level that risks generating excessive inflationary pressure. If the Bank of England slams on the brakes, the economy could shift down, slowing job growth. So wage increases need to hit the sweet spot of protecting living standards without prompting policymakers to boost interest rates swiftly.

Another question is how much further labour demand can strengthen without an accompanying pick-up in labour supply. So far, hiring has hit record levels, with 2.2 million people starting new jobs in the third quarter of 2021. But persistent worker shortages, along with supply chain disruptions and rising input costs, could impair the ability of businesses to expand further. This may act as a drag on growth and, ultimately, feed back into slower hiring. As a result, sectors suffering chronic labour shortages will be pushing for greater flexibility in the government’s post-Brexit migration regime.

Methodology

The relative jobseeker interest metric takes the average number of clicks per job posting for each job category relative to 1 February, 2020, divided by national clicks per posting relative to the same time period. Both clicks and job postings are 28-day moving averages of seasonally adjusted data.

A positive change means the average job posting in a category is now more attractive to job seekers relative to the average posting than before the pandemic. A negative change indicates that the category has lost interest relative to the average posting since 1 February, 2020. By construction, the national average across all sectors is zero.

Skill level is derived from the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC). Major groups 1 to 3 are classified as high skill, major groups 4 to 6 are classified as medium skill and major groups 7 to 9 are classified as low skill.